Half an hour into my interview with Gilbert and George, something unexpected happens: they disagree. Gilbert Prousch is talking about their urge to provoke and outrage. “We see all the other artists as somehow meaningless,” says the 74-year-old, his Italian accent still strong. Gilbert grew up in a tiny village in the Dolomites and attended art colleges all over Europe, before meeting George in London during the autumn of 1967, when they were both studying advanced sculpture at St Martin’s.

“They’re not asking any questions,” continues Gilbert. “We are quite disillusioned with that kind of art ourselves. We want an art that is in your face: aggressive. We are confrontational. Freedom of speech, we call it. To say what we want.”

George Passmore – who is from Devon and whose genteel enunciation suits the duo’s old-world style as crisply as the suits they are wearing here in their home at 10 in the morning – doesn’t like where this is going. “I think we’re greatly loved and admired by the vast general public,” interrupts the 75-year-old.

“Nyaaagh,” splutters Gilbert, getting the message. “Maybe ... Aggressive is not ...”

But “aggressive” really is the right word for some of their very best work. It is also the correct word for their attitude to other people, I find, as they let rip about various adversaries from former Tate boss Nicholas Serota, who they can’t forgive for trying to make them have a retrospective at Tate Britain instead of Tate Modern (they won), to anyone who uses the word “gentrification”. My casual reference to the rampant gentrification of their east London neighbourhood unleashes a torrent.

George: “We’re very against the term gentrification. We think it’s classist and sexist, because you’d never say ladyfication.” Gilbert: “Or Jewification.” George: “Or blackification. Or Bangladeshification. They’ve only got it in for white people. It’s extraordinary. It’s punishing the honkies.”

They used to say a lot of this sort of garbage in interviews – or, anyway, a lot more of their less attractive views used to get published. They didn’t hold back with me, so do their many interviews tend to kindly edit such stuff out? Back in 1981, they told the writer Gordon Burn that fascism is a “life force”. Gradually, however, the thornier side of Gilbert and George has passed into memory, especially since they got that Tate Modern show in 2007.

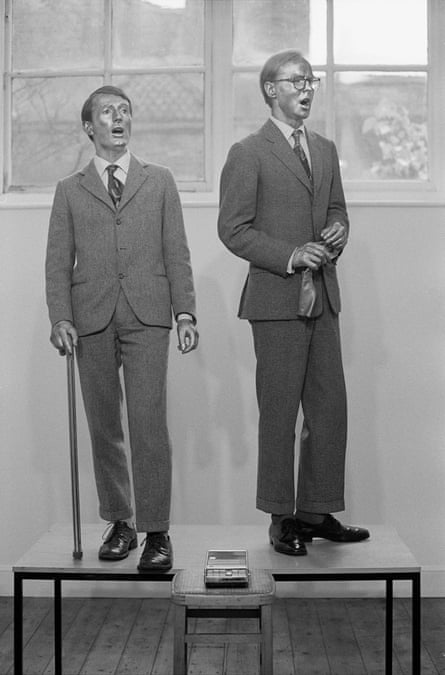

The pair have now been elevated to the status of a national treasure. Their 50th anniversary this autumn has confirmed it. A BBC interviewer relished their “softer, gentler side” as they opened The General Jungle, an exhibition of their charming early drawings. It has also been a chance to look back on The Singing Sculpture, the universally admired 1970 performance that made them famous, in which they posed as metal-faced android outsiders singing along to a record of the old music hall classic Underneath the Arches.

But are they really so lovable? And would they be such good artists if they were? This talk of aggression goes to the heart of what 50 years of Gilbert and George is really about. For the wrong Gilbert and George are being celebrated. Sure, The Singing Sculpture popularised the strange new idea that art could be anything. No doubt to this day, they are in some sense “living sculptures”, still going on their walks through Spitalfields collecting leaves, lichen and nitrous oxide canisters.

But since the 70s they have made “pictures”, often on a colossal scale, montaging photographs they take on the streets of London with images of themselves to create shocking, comic and tragic portraits of their times. These history paintings – the photographic equivalents of the murals and epic canvases that in days gone by used to record battles and parades – are the most evocative and detailed artistic representation of the moods and mores of modern Britain. Their latest works, The Beard Pictures, skewer today’s fetish for male facial hair – and use it to satirise everything from religion to Jeremy Corbyn.

Far from damaging their art, their dubious opinions have given it a lot of its strength. Some of their most powerful and truthful works were made when they were drawn to something much darker than the David Cameron poster in their studio would suggest. The reason Burn asked them about fascism was because, in such pictures as Four Knights and Patriots, they portrayed skinheads not just with romantic regard but apparent nationalist fervour.

When I ask about these works, George says: “The world had skinheads and the world has skinheads.” It is a point that goes to the essence of their art. Everything in Gilbert and George’s pictures comes from the world. Even the most bizarre, contorted images are enlarged, coloured versions of simple photographs of ordinary things, from toy soldiers to medals to barbed wire. In their tiny garden, they show me a tray of bright green lichen they’ve collected locally. This humble life form – is it animal, wonders George, or vegetable? – will be photographed up close and find its way into a picture. Similarly, in a recent work, they sport beards made of leaves.

Like Andy Warhol, who they dismiss as a commercialist, they record the world around them with hypnotic, mesmerising directness. If Warhol was a “mirror” whose paintings passively reflect their time, Gilbert and George are more like a hall of mirrors in a mad British funfair, whose grotesque reflections reveal disconcerting truths. Today, Patriots and Four Knights do not look like celebrations of skinheads, let alone the racist right. They look like far-seeing images of a divided, desperate Britain.

Anger blazes in all the pictures Gilbert and George made back then. One 1977 work is called Cunt Scum. These words appear in graffiti they photographed, in a montage that also includes tense London crowds, a policeman, and a row of homeless men sitting by a road. It looks like it’s about to explode into a riot. Their Red pictures from the same time are just as threatening. Yet, with hindsight, they seem to truthfully capture Britain in the turbulent age of the IRA and punk. In words the Sex Pistols could have scrawled themselves, one work even asks: “Are you angry or are you boring?”

Were they drawn to punk? No, they say, although they went to the clubs “just because of the dirty nightlife”. Malcolm McLaren, the intellectual progenitor of punk, was a fan of their early work. He was influenced, they suggest, by their Drinking Sculptures which celebrate self-destruction.

The pair are, in fact, fascinated by history. George, says Gilbert proudly, gets up at 5am every day to read 19th-century literature. George shows me the Walter Scott novel he’s currently tackling. “You can read novels to study history much better than history books,” he says. You could make the same claim of their art: the strange and wild images they collect on their walks come together as a vast and scary novel, with themselves as heroes or antiheroes.

George’s reading is all part of his cultivated persona, which evokes a Britain that vanished about the same time as TV was invented. The pair have not been to the cinema since 1979, but one thing they saw recently in the West End was a revival of the Edwardian-set musical Half a Sixpence. “Now it’s not with Tommy Steele, of course,” says George. “It’s with Charlie Stemp, who’s an amazing, magical performer. We even became stage-door johnnies, waiting to see him.” In the new year, they are going to see Stemp in Dick Whittington, which they regard as “our pantomime” because, like its hero, they made it from nothing in “the thing that’s called London”.

This sense of struggling, of standing firm in the face of adversity, may be the key not only to their art but to their shared life. The idea they have of themselves as embattled takes a particularly dark twist as they rail against religions, including Christianity. “They smacked our door in because we are non-believers,” Gilbert suddenly intones, almost as if chanting. “Muslims,” he expands. “Maybe 10 years ago.”

“All non-Muslim houses in the street were kicked in,” adds George. “You sound surprised. They used to say, ‘Fuck off out of this, this is a holy place.’”

That’s not the only violent tale they tell. When they first moved to the East End, they say, the “cockneys” used to call them “faggots and poofs” and “would throw tea in your face”.

They say their enemies did them a favour, though. They had to fight for themselves. They are still fighting. Having to stick together – against critics, abusers and hostile neighbours – helped them create their own world. And most couples of their generation broke up after all. “It was the permissive generation,” says George. “People changed partners once a year.”They’re particularly excited by an opera about them called The Naked Shit Songs. Recently premiered in Amsterdam, the work recreates their 1996 TV interview with Theo van Gogh, the controversial film-maker who was later murdered by Mohammed Bouyeri. “He spoke against Islam and we were very supportive of it,” says George. “This was before the twin towers, before we had our door kicked in.” Don’t you know, thundered Van Gogh, they’re against gay sex? “And we said, ‘Yes, but they still do it.’”

That’s Gilbert and George: wading into the toughest fights and always coming out with their suits immaculate.

- Gilbert & George, The Beard Pictures and Their Fuckosophy is at White Cube Bermondsey, London, from 22 November to 28 January. The General Jungle or Carrying on Sculpting is at Lévy Gorvy, London, until 2 December.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion