One reason Jeffrey Smart paintings have gone up in price is because that’s what happens when there’s a big show, such as the one at the National Gallery of Australia celebrating 100 years since the late artist’s birth. Another reason is love. Specifically, how the love for Smart’s paintings stays unrequited because it’s never wholly fulfilled.

“I’ve really noticed with this show that private collectors hold on very closely, it’s been a bit of a wrench,” says the exhibition’s co-curator Deborah Hart. “A lot of people really love them and maybe that’s got to do with their open-endedness. I imagine if you lived with [a Smart painting] you’d keep seeing things a little bit differently in the work.” Or, as the exhibition’s second curator, Rebecca Edwards, writes in her catalogue essay: “Smart’s work is an inscrutable and open-ended riddle.”

Titled Jeffrey Smart, the NGA exhibition is not a retrospective so “we don’t have that obligation and pressure to include every large important work”, Hart says. Yet many are among the 125 works anyway, including Smart’s very funny Portrait of Clive James, in which James is placed on a far-off highway overpass, comically dwarfed by a corrugated iron fence. Looking at it, you wonder if Smart’s wry idea of what constituted a portrait might have influenced bolder departures from tradition later, such as Justine Varga’s controversial 2017 Olive Cotton award-winning photographic portrait of her grandmother, made from scribble and spit.

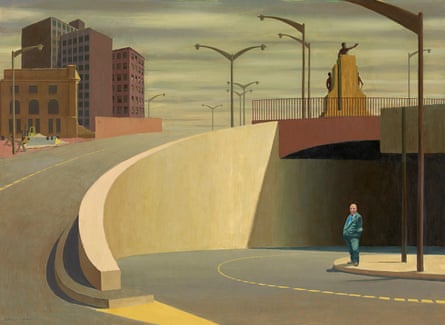

His Cahill Expressway from 1962 is here too, its stout male businessman standing alone in a Sydney gripped by an unnerving stasis and emptiness that, until 2020, seemed a wholly surreal scene. Not any more.

Smart was born in Adelaide in 1921. The exhibition explores the arc of his 70-year practice, concluding with his last work Labyrinth, painted from his wheelchair when he was 89 years old. While the curation does not serve up the comfort food of a strict chronology, there is a smooth flow between “the ideas and motifs that really interested him”, says Edwards. Preliminary studies and sketches reveal his meticulous preparations, and the trajectory of his life is shown – from Adelaide to Sydney to Italy, where he lived for 45 years until his death in 2013.

“You’re not going to leave wondering, ‘Who was Jeffrey Smart? What did he do?’” Hart says. “We didn’t want to go too wild.” Good plan. Life’s wild enough right now. The “heightened stillness” of Smart’s urban visions, as Hart describes it, is plenty to absorb.

In any case, Smart liked his paintings being left to speak for themselves. “Jeffrey Smart made it a principle to not explain his art verbally, much to the chagrin of art critics, journalists and documentary makers,” writes the Smart estate archivist, Stephen Rogers, in the catalogue. “Any direct question as to the meaning of a work was pushed aside.” His audience was thus able to “create their own story”.

Five sound artists have done just that, producing two compositions each in response to 10 paintings, commissioned through the experimental Melbourne-based sound organisation Liquid Architecture. “The lovely thing is it makes you slow down, because you want to listen to the music and look at the work at the same time,” Hart says. Edwards says the process of looking and listening made her “notice things I’d never noticed before”.

Smart loved opera and Bach but most of all Wagner; he travelled with his partner, Ermes De Zan, for performances of the Ring Cycle in cities around the world. When a documentarian once suggested the “evident stillness” of his work should be “echoed by a complementary silence”, Smart disagreed. “What I’d love to have is a background … [Wagner’s] Parsifal would be beautiful.” The contemporary compositions “are not what Jeffrey might have personally chosen”, Hart says. He may have been “quite shocked”, says Edwards.

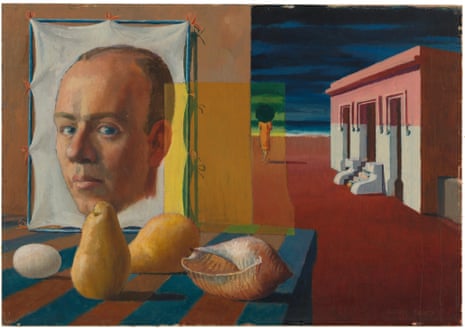

Or maybe not. Smart’s study of art, love of philosophy and cinema, and reading of profound texts continued even as he aged, indicating openness and humility. His works often reference art movements such as abstract expressionism and pop art, and he replicated both The Dance (Matisse) and Mona Lisa (Da Vinci) as posters in paintings. His 1972 work The Painted Factory is a nod to René Magritte with its figure holding up a painting within a painting – and, depending on your eyesight, another painting within that. Sound art about art about art may well have delighted him.

The only cubist work he produced is exhibited too, alongside a similar work by his Adelaide teacher, Dorrit Black. In the early 1940s Black taught Smart the principles of the golden mean and dynamic symmetry and, while a lot is heard about the impact of poet TS Eliot on Smart’s thinking, Black was a seminal influence too.

“He really admired women artists – Dorrit Black, Jacqueline Hick, Jean Bellette, you could go on,” Hart says. “People now associate him with being such a successful artist but in the 40s and 50s he was really struggling … living in boarding houses and trying to make ends meet. Women meant a lot to him in his life and people who supported him like [artist] Judy Cassab when he was really struggling in Sydney, he very much acknowledges their support and his admiration, especially for Dorritt.”

Jeffrey Smart is showing at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra from 11 December to 15 May

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion