Chris Riddell opens a sketchbook and flicks to a drawing he wants to show me, in which a rather ordinary-looking middle-aged man is wrapped in the long arms of a skinnier, taller, hairier one. The first figure is a self-portrait, the second is of Russell Brand.

“This is what he does to me now, because he knows I’m very inhibited: he gives me these big man hugs and bearded kisses. It’s very embarrassing,” says Riddell, the award-winning writer and illustrator of more than 100 children’s books, and for nearly 20 years the Observer’s political cartoonist.

Riddell met Brand for the first time earlier this year, in a private members’ club in London – “slightly glitzy, not my preferred milieu”, he tells me in the sitting room of the house in Brighton he shares with his wife, illustrator Jo Burroughes. But first impressions were good, and last month Brand and Riddell officially became an item – as author and illustrator of Brand’s first children’s book, a colourful retelling of The Pied Piper of Hamelin.

In another of Riddell’s sketchbooks the two sit side by side on a sofa with labels: “fashionably ripped jeans” (Brand), “unfashionably unripped jeans” (Riddell). “I thought he could be a bit starry; I anticipated strange, idiosyncratic demands,” recalls the cartoonist, “but it was the opposite of that: it was permissive, it was exciting, it was frenetic.”

Last month they took to the stage at the Albert Hall: Brand read his story – the thrust of which is that Hamelin is a vile town, whose people deserve to have their children stolen – and wandered around charming the audience; Riddell made sketches that were projected on to the wall.

Some reviewers thought Riddell’s drawings were the best thing about the book, and were scathing about the text, but Riddell says Brand inspired him. “It was almost impossible not to have him in mind when drawing the piper,” he says, “and yet I didn’t want to be too obvious about it. He eased me away from a traditional approach into something less expected: ‘Let’s not have a little German town with gabled houses, let’s not have a pied piper with a feathered hat and long sleeves.’ He was very specific about how he saw the piper, and described the costume down to the utility belt and bowler hat from A Clockwork Orange.”

On the wall of Riddell’s studio, at the bottom of the garden, is a black-and-white design he made for the fracking protests at Balcombe. So does he share Brand’s anti-establishment views? “The notion that you should disengage is wrong,” he says. “You should challenge and protest; but to be fair to Russell, he does. I think the message of the books is at the core of what he has been doing on and off: questioning power. That’s not a bad message.”

Riddell was born in South Africa in 1962, the youngest of three. His father was an Anglican vicar involved in anti-apartheid politics, but in the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre the family decided to leave. Riddell grew up in Brixton, south London, went to a local grammar school before it turned comprehensive, and then “ran off to art school”.

A keen though late reader, he hoped to work with books in some way; it took an art teacher to nudge him away from an English degree towards an art foundation course in Surrey: “I was such a conformist, it seemed a very transgressive thing to do … I remember being hugely excited on the first day, seeing a chap dressed like Adam Ant.”

In our age of loans and fees, “go to art school for art school’s sake!” was his advice to daughter Katie, now studying illustration in Manchester, with whom he hopes to collaborate (following the example of other father-daughter partnerships, including Allan and Jessica Ahlberg).

Raymond Briggs was Riddell’s tutor during his degree at Brighton, and when London publishers came to court Briggs – famous for When the Wind Blows and The Snowman – he made introductions: Riddell’s first commission, for a book about giants, came from Sebastian Walker of Walker Books on one such visit.

Fantastic creatures and monsters of all sorts remain a staple, along with the crazy contraptions that are another classic element of the children’s fantasy tradition (Riddell jokes that “anyone can look through my sketchbooks as long as they don’t have a background in psychiatric medicine”). John Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland are an all-time favourite. So is William Heath Robinson, a copy of whose The Adventures of Uncle Lubin Riddell showed to Brand. Tony Hart was another inspiration, along with Arnold Lobel and Quentin Blake.

Riddell draws in pencil, inks over the lines with a brush, and adds colour, often blue and yellow, last: “I’m not a painter by any stretch of the imagination; I’m a dyed-in-the-wool traditional illustrator, and I begin with black and white. If I need colour, I add it over the top. There’s a calligraphic element to it … it’s about the texture of lines on the page.”

Like many fantasy images, Riddell’s are very detailed, and he is a prolific and humorous user of words: labels, literary quotations, puns, funny names, footnotes, headings in neat, spidery writing on scrolls adorned with curlicues. He loves stationery, writes everything by hand in beautiful hardback sketchbooks, and can spend hours inking in – “I love it, it’s like meditation” – while listening to Radio 3. But he can work fast when he needs to: “I’m a cartoonist through and through. My default mode is: there is a deadline, it needs to go in the paper, let’s get it done. With books it’s useful to have that higher gear to switch to.”

The hectic schedule for The Pied Piper persuaded him to try a pastel pencil; occasionally he uses an art pen for very fine lines, “though I don’t like using them, because they’ve got a mechanical-looking line; the lovely thing about a paintbrush is its fluidity, it gives a lyrical quality”.

Riddell wrote his first children’s story, Mr Underbed, because another grandee of children’s publishing, Klaus Flugge of Andersen Press, asked him to. Last year he won the Costa children’s book award for Goth Girl and the Ghost of a Mouse, a gothic parody created with daughter Katie in mind, which he chooses when asked to name his favourite of his own books. But in general, he admits with appealing frankness: “the writing process isn’t something I’m in love with. I’m an illustrator who writes.”

More than 20 years ago, he met the writer Paul Stewart when picking up his son from nursery. Together, they developed the hugely popular Edge Chronicles fantasy series, and today Stewart lives four doors down. The idea for their flat-earth world was Riddell’s, and began with a map, dismissed as unworkable by a publisher. But he and Stewart began to have “huge fun”, meeting to discuss it in a local pub. By the time they had finished the first instalment of what would become a 14-part series (with books 13 and 14 still to come), Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was a bestseller, and publishers had changed their tune.

“JK Rowling is the patron saint,” he says. “I call it the happy time. JK, for understandable reasons, thought she needed some time off, and there was this wonderful interregnum when the rest of us saw our book sales just take off. It was brilliant. I won’t have a word said against her. There’s a generation of us who came in on that breaking wave.”

But by the time Riddell won his first big prize, a Kate Greenaway medal for Pirate Diary in 2001, he was anxious: “I was getting that feeling – ‘What’s wrong with me? I showed such promise’ – so that was a huge relief. You only need to win it once and then you’re all right … you’re validated.”

Successes have multiplied: another Kate Greenaway medal for illustrating a new version of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels; prizes for Fergus Crane (another collaboration with Stewart) and Ottoline and the Yellow Cat (a crime caper written by Riddell, involving a gang of poker-playing dogs), as well as Goth Girl.

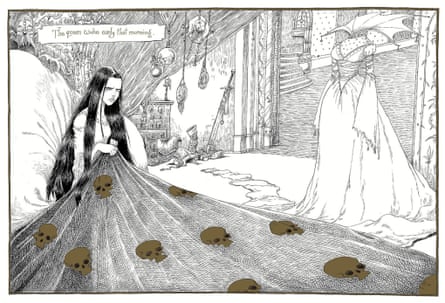

In 2010 he was again shortlisted for the Greenaway medal for his illustrations in Neil Gaiman’s bestseller The Graveyard Book. In October, the two brought out The Sleeper and The Spindle. A modern fairytale that blends elements from Sleeping Beauty and Snow White, it is drawn by Riddell in black and white with flashes of gold, and contains one of his most striking images to date, a double-page spread in which an enchanted sleeper is woken by a kiss not from a prince but from a queen.

Early in his career Riddell illustrated editions of Peter Pan and Treasure Island. Next year he will tackle The Emperor’s New Clothes, the second of Russell Brand’s Trickster Tales, in which readers will presumably be invited to feel an unfamiliar degree of sympathy with the dishonest tailors. After that, perhaps, Rumpelstiltskin.

“I love the notion that you have a canon, you have fairytales that have been done hundreds of times and you are given permission to do your version,” he says. “It’s an accretion. You build on the past.”

These days he doesn’t have to pitch ideas; instead, publishers take him out to lunch and ask what he’s been thinking about. His position, he says, is “hugely privileged”, including his weekly deadline for the Observer: “it’s the paper my father read”.

The night before our interview, he was on a train back to Brighton after a day touring bookshops when his phone rang. It was Gaiman, calling to read aloud a story he was working on. Riddell had one of those moments of not quite believing his luck. “He asked if I was interested in the story, and I said, ‘Am I?!’”

But he still has the freelancer’s fear of work drying up, and had to take the manuscript of Goth Girl into a local school to reassure himself it wouldn’t flop. “I call my style the high facetious,” he says. “Facetious is OK, but I don’t want to look a fool.”

There is time for a self-deprecating parting shot on the doorstep – “I look forward to your Lynn Barber-esque dismantling of this pompous man” – then he heads back inside to finish a cartoon, with a caption from George Orwell (“Alas! Wigan pier had been demolished …”), in which a tail-coated chancellor George Osborne blows up the welfare state.

Click here to order The Sleeper and the Spindle for £9.49 (RRP £12.99)

Click here to order The Pied Piper of Hamelin for £11.99 (RRP £14.99).

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion