They have been called patriarchal, formulaic and lightweight – and that’s the polite description. But an academic is making the case for Mills & Boon romances to be considered as feminist texts that are the literature of protest rather than mere escapism.

Val Derbyshire said the books should be read by women and men with pride rather than guilty embarrassment. “It is such a shame that they have been so vilified, and that people treat them as trash and the black sheep of the literary family,” she added. “There really is literary value in them, which is why I continue to read them.”

Derbyshire is to lead two events at Sheffield University’s Festival of the Mind next month, in which she will make the literary and feminist case for the thousands of books in Mills & Boon’s vast back catalogue.

“They are definitely not anti-feminist,” she argued. “These are novels written primarily by women, for women – why would they set out to insult their target audience? It doesn’t make any sense.”

Instead, they are largely stories of feminist triumph, with the brooding male hero often forced to acknowledge his sexism and change his ways. “They foreground the female and they are stories about women and for women,” Derbyshire said.

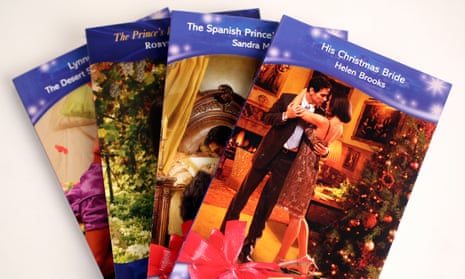

Some commentators have criticised the books as having needy heroines, desperate for the love of a brutish man. Derbyshire, who has read hundreds of Mills & Boon novels, said: “I suspect people who have never read them would say that. There are an awful lot of people who think they know what is going on in a Mills & Boon by just looking at the covers.”

The novels also tackle important issues head-on, the academic said. For example, Time Fuse (1985), by Derbyshire’s favourite Mills & Boon author, the prolific Penny Jordan, tackles the subject of rape, exposing the shocking way it was dealt with by courts and how women were blamed.

This is the “literature of protest”, said Derbyshire, with Jordan addressing the issue in “the only way she knew – through her romantic novels”.

Another criticism of the books is that they are formulaic. Again, Derbyshire said that people need to read them. “Penny Jordan wrote 187 novels over three-and-a-half decades. She couldn’t have remained so enduringly popular if she was churning out the same things. She was innovating all the time.”

Derbyshire was 14 when she read her first Mills & Boon, Escape from Desire (1982) by Jordan. “I asked my sister a difficult question on the facts of life and she said ‘read this’,” the academic said. “It raised more questions than it answered, I’ve got to be honest, but it was just so much fun I’ve been hooked ever since.”

Derbyshire is a doctoral researcher at Sheffield, studying the works of the 18th-century Romantic poet and novelist, Charlotte Turner Smith, a writer who also used romantic fiction as the literature of protest.

Mills & Boon was created in 1908 by Gerald Mills and Charles Boon. Beginning as a general publisher, it made romance its principal concern in the 1930s and has gone on to publish thousands of easy-reading novels with titles such as Staff Nurses in Love, Tethered Liberty, Italian Invader and The Trouble with Trent.

Derbyshire, a married mother of two sons, said she always reached for a Mills & Boon if she was fed up. “They always cheer me up, they are always an enormous amount of fun and they are always much more intelligent than you think they will be. There’s always something to discover in them.”

She believes historians should also read the books because they are so of their time, capturing contemporary anxieties and societal and fashion trends that are often forgotten. Anyone studying the social history of the late 70s, for example, could do worse than read Roberta Leigh’s Man Without a Heart, Derbyshire said – a book rich with romance and developments in the British car industry.

More than anything, Derbyshire urged readers not to feel ashamed. “There is a huge amount of snobbery,” she said. “It exists not just in academia and literature circles but generally. Some people do not feel comfortable sitting on a bus reading a Mills & Boon and that is a shame. If you have never read one, how can you know?”