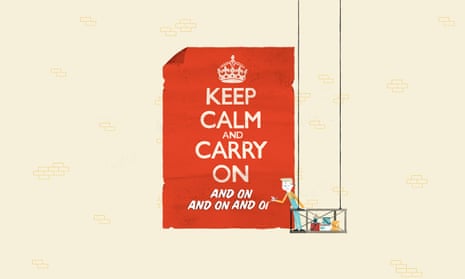

To get some sense of just what a monster it has become, try counting the number of times in a week you see some permutation of the “Keep Calm and Carry On” poster. In the last few days I’ve seen it twice as a poster advertising a pub’s New Year’s Eve party, several times in souvenir shops, in a photograph accompanying a Guardian article on the imminent doctors’ strike (“Keep Calm and Save the NHS”) and as the subject of too many internet memes to count. Some were related to the floods – a flagrantly opportunistic Liberal Democrat poster, with “Keep Calm and Survive Floods”, and the somewhat more mordant “Keep Calm and Make a Photo of Floods”. Then there were those related to Islamic State: “Keep Calm and Fight Isis” on the standard red background with the crown above; and “Keep Calm and Support Isis” on a black background, with the crown replaced by the Isis logo. Around eight years after it started to appear, it has become quite possibly the most successful meme in history. And, unlike most memes, it has been astonishingly enduring, a canvas on to which practically anything can be projected while retaining a sense of ironic reassurance. It is the ruling emblem of an era that is increasingly defined by austerity nostalgia.

I can pinpoint the precise moment at which I realised that what had seemed a typically, somewhat insufferably, English phenomenon had gone completely and inescapably global. I was going into the flagship Warsaw branch of the Polish department store Empik and there, just past the revolving doors, was a collection of notebooks, mouse pads, diaries and the like, featuring a familiar English sans serif font, white on red, topped with the crown, in English:

KEEP CALM

AND

CARRY ON

It felt like confirmation that the image had entered the pantheon of truly global design “icons”. As an image, it was now up there alongside Rosie the Riveter, the muscular female munitions worker in the US second world war propaganda image; as easily identifiable as the headscarved Lily Brik bellowing “BOOKS!” on Rodchenko’s famous poster. As a logo, it was nearly as recognisable as Coca-Cola or Apple. How had this happened? What was it that made the image so popular? How did it manage to grow from a minor English middle-class cult object into an international brand, and what exactly was meant by “carry on”? My assumption had been that the combination of message and design were inextricably tied up with a plethora of English obsessions, from the “blitz spirit”, through to the cults of the BBC, the NHS and the 1945 postwar consensus. Also contained in this bundle of signifiers was the enduring pretension of an extremely rich (if shoddy and dilapidated) country, the sadomasochistic Toryism imposed by the coalition government of 2010–15, and its presentation of austerity in a manner so brutal and moralistic that it almost seemed to luxuriate in its own parsimony. Some or none of these thoughts may have been in the heads of the customers at Empik buying their printed tea towels, or they may have just thought it was funny. However, few images of the last decade are quite so riddled with ideology, and few “historical” documents are quite so spectacularly false.

The Keep Calm and Carry On poster was not mass-produced until 2008. It is a historical object of a very peculiar sort. By 2009, when it had first become hugely popular, it seemed to respond to a particularly English malaise connected directly with the way Britain reacted to the credit crunch and the banking crash. From this moment of crisis, it tapped into an already established narrative about Britain’s “finest hour” – the aerial Battle of Britain in 1940-41 – when it was the only country left fighting the Third Reich. This was a moment of entirely indisputable – and apparently uncomplicated – national heroism, one that Britain has clung to through thick and thin. Even during the height of the boom, as the critical theorist Paul Gilroy flags up in his 2004 book, After Empire, the blitz and the victory were frequently invoked, made necessary by “the need to get back to the place or moment before the country lost its moral and cultural bearings”. The years 1940 and 1945 were “obsessive repetitions”, “anxious and melancholic”, morbid fetishes, clung to as a means of not thinking about other aspects of recent British history – most obviously, its empire. This has only intensified since the financial crisis began.

The “blitz spirit” has been exploited by politicians largely since 1979. When Thatcherites and Blairites spoke of “hard choices” and “muddling through”, they often evoked the memories of 1941. It served to legitimate regimes that constantly argued that, despite appearances to the contrary, resources were scarce and there wasn’t enough money to go around; the most persuasive way of explaining why someone (else) was inevitably going to suffer. Ironically, however, this rhetoric of sacrifice was often combined with a demand that consumers enrich themselves – buy their house, get a new car, make something of themselves, “aspire”. Thus, by 2007‑08, when the “no return to boom and bust” promised by Gordon Brown appeared to be abortive (despite the success of his very 1940s alternative of nationalising the banks and thus “saving capitalism”), the image started to become popular. It is worth noting that shortly after this point, a brief series of protests were being policed in increasingly ferocious ways. The authorities were allowed to make use of the apparatus of security and surveillance, and the proliferation of “prevention of terrorism” laws set up under the New Labour governments of 1997–2010, to combat any sign of dissent. In this context the poster became ever more ubiquitous, and, peculiarly, after 2011, it began to be used in what few protests remained, in an only mildly subverted form.

The Keep Calm and Carry On poster seemed to embody all the contradictions produced by a consumption economy attempting to adapt itself to thrift, and to normalise surveillance and security through an ironic, depoliticised aesthetic. Out of apparently nowhere, this image – combining bare, faintly modernist typography with the consoling logo of the crown and a similarly reassuring message – spread everywhere. I first noticed its ubiquity in the winter of 2009, when the poster appeared in dozens of windows in affluent London districts such as Blackheath during the prolonged snowy period and the attendant breakdown of National Rail; the implied message about hardiness in the face of adversity and the blitz spirit looked rather absurd in the context of a dusting of snow crippling the railway system. The poster seemed to exemplify a design phenomenon that had slowly crept up on us to the point where it became unavoidable. It is best described as “austerity nostalgia”. This aesthetic took the form of a yearning for the kind of public modernism that, rightly or wrongly, was seen to have characterised the period from the 1930s to the early 1970s; it could just as easily exemplify a more straightforwardly conservative longing for security and stability in hard times.

Unlike many forms of nostalgia, the memory invoked by the Keep Calm and Carry On poster is not based on lived experience. Most of those who have bought this poster, or worn the various bags, T-shirts and other memorabilia based on it, were probably born in the 1970s or 1980s. They have no memory whatsoever of the kind of benevolent statism the slogan purports to exemplify. In that sense, the poster is an example of the phenomenon given a capsule definition by Douglas Coupland in 1991: “legislated nostalgia”, that is, “to force a body of people to have memories they do not actually possess”. However, there is more to it than that. No one who was around at the time, unless they had worked at the department of the Ministry of Information, for which the poster was designed, would have seen it. In fact, before 2008, few had ever seen the words “Keep Calm and Carry On” displayed in a public place.

The poster was designed in 1939, but its “official website”, which sells a variety of Keep Calm and Carry On merchandise, states that it never became an official propaganda poster; rather, a handful were printed on a test basis. The specific purpose of the poster was to stiffen resolve in the event of a Nazi invasion, and it was one in a set of three. The two others, which followed the same design principles, were:

YOUR COURAGE

YOUR CHEERFULNESS

YOUR RESOLUTION

WILL BRING

US VICTORY

and:

FREEDOM IS

IN PERIL

DEFEND IT

WITH ALL

YOUR MIGHT

Both of these were printed up, and “YOUR COURAGE … ” was widely displayed during the blitz, given that the feared invasion did not take place after the German defeat in the Battle of Britain. You can see one on a billboard in the background of the last scene of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1943 film, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, when the ageing, reactionary but charming soldier finds his house in Belgravia bombed. Of the three proposals, KEEP CALM AND CARRY ON was discarded after the test printing. Possibly, this was because it was considered less appropriate to the conditions of the blitz than to the mass panic expected in the event of a German ground invasion. The other posters were heavily criticised. The social research project Mass Observation recorded many furious reactions to the patronising tone of YOUR COURAGE … and its implied distinction between YOU, the common person, and US, the state to be defended. Anthony Burgess later claimed it was rage at posters like this that helped Labour win such an enormous landslide in the 1945 election. We can be fairly sure that if KEEP CALM AND CARRY ON had been mass-produced, it would have infuriated those who were being implored to be calm. Wrenched out of this context and exhumed in the 21st century, however, the poster appears to flatter, rather than hector, the public it is aimed at.

One of the few test printings of the poster was found in a consignment of secondhand books bought at auction by Barter Books in Alnwick, Northumberland, which then created the first reproductions. First sold in London by the shop at the Victoria and Albert Museum, it became a middlebrow staple when the recession, initially merely the slightly euphemistic “credit crunch”, hit. Through this poster, the way to display one’s commitment to the new austerity regime was to buy more consumer goods, albeit with a less garish aesthetic than was customary during the boom. This was similar to the “Keep calm and carry on shopping” commanded by George W Bush both after September 11 and when the sub-prime crisis hit America. The wartime use of this rhetoric escalated during the economic turmoil in the UK; witness the slogan of the 2010-15 coalition government, “We’re all in this together”. The power of Keep Calm and Carry On comes from a yearning for an actual or imaginary English patrician attitude of stiff upper lips and muddling through. This is, however, something that largely survives only in the popular imagination, in a country devoted to services and consumption, where elections are decided on the basis of house-price value, and given to sudden, mawkish outpourings of sentiment. The poster isn’t just a case of the return of the repressed, it is rather the return of repression itself. It is a nostalgia for the state of being repressed – solid, stoic, public spirited, as opposed to the depoliticised, hysterical and privatised reality of Britain over the last 30 years.

At the same time as it evokes a sense of loss over the decline of an idea of Britain and the British, it is both reassuring and flattering, implying a virtuous (if highly self-aware) consumer stoicism. Of course, in the end, it is a bit of a joke: you don’t really think your pay cut or your children’s inability to buy a house, or the fact that someone somewhere else has been made homeless because of the bedroom tax, or lost their benefit, or worked on a zero-hours contract, is really comparable to life during the blitz – but it’s all a bit of fun, isn’t it?

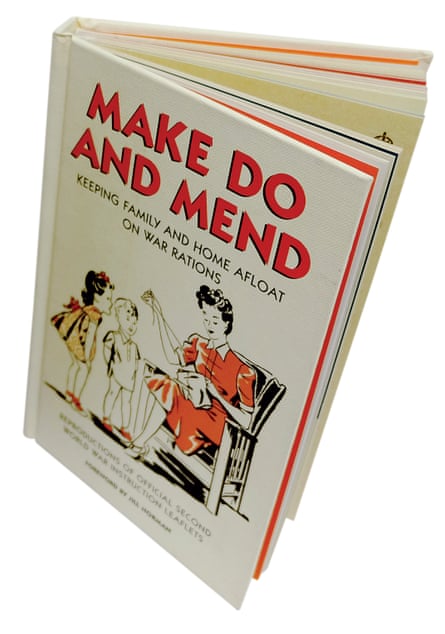

The Keep Calm and Carry On poster is only the tip of an iceberg of austerity nostalgia. Although early examples of the mood can be seen as a reaction to the threat of terrorism and the allegedly attendant blitz spirit, it has become an increasingly prevalent response to the uncertainties of economic collapse. Interestingly, one of the first areas in which this happened was the consumption of food, an activity closely connected with the immediate satisfaction of desires. Along with the blitz came rationing, which was not fully abolished until the mid-1950s. Accounts of this vary; its egalitarianism meant that while the middle classes experienced a drastic decline in the quality and quantity of their diet, for many of the poor it was a minor improvement. Either way, it was a grim regime, aided by the emergence of various byproducts and substitutes – Spam, corned beef – which stuck around in the already famously dismal British diet for some time, before mass immigration gradually made eating in Britain a less awful experience. In the process, entire aspects of British cuisine – the sort of thing listed by George Orwell in his essay “In Defence of English Cooking” such as suet dumplings, Lancashire hotpot, Yorkshire pudding, roast dinners, faggots, spotted dick and toad in the hole – began to disappear, at least from the metropoles.

The figure of importance here is the Essex-born multimillionaire chef and Winston Churchill fan, Jamie Oliver. Clearly as decent and sincere a person as you’ll find on the Sunday Times Rich List, his various crusades for good food, and the manner in which he markets them, are inadvertently telling. After his initial fame as a New Labour‑era star, a relatively young and Beckham-coiffed celebrity chef, his main concern (aside from a massive chain-restaurant empire that stretches from Greenwich Market in London to the Hotel Moskva in Belgrade) has been to take “good food” – locally sourced, cooked from scratch – from being a preserve of the middle classes and bring it to the “disadvantaged” and “socially excluded” of inner-city London, ex-industrial towns, mining villages and other places slashed and burned by 30-plus years of Thatcherism. The first version of this was the TV series Jamie’s School Dinners, in which a camera crew documented him trying to influence the school meals choices of a comprehensive in Kidbrooke, a poor, and recently almost totally demolished, district in south-east London. Notoriously, this crusade was nearly thwarted by mothers bringing their kids fizzy drinks and burgers that they pushed through the fences so that they wouldn’t have to suffer that healthy eating muck.

The second phase was the book, TV series and chain of shops branded as the Ministry of Food. The name is taken directly from the wartime ministry charged with managing the rationed food economy of war-torn Britain. Using the assistance of a few public bodies, setting up a charity, pouring in some coalfield regeneration money and some cash of his own, Oliver planned to teach the proletariat to make itself real food with real ingredients. One could argue that he was the latest in a long line of people lecturing the lower orders on their choice of nutrition, part of an immense construction of grotesque neo-Victorian snobbery that has included former Channel 4 shows How Clean Is Your House?, Benefits Street and Immigration Street, exercises in “Let’s laugh at picturesque prole scum”. But Oliver got in there, and “got his hands dirty”.

However, the story ended in a predictable manner: attempts to build this charitable action into something permanent and institutional foundered on the disinclination of any plausible British government to antagonise the supermarkets and sundry manufacturers who funnel money to the two main political parties. The appeal to a time when things such as food and information were apparently dispensed by a benign paternalist bureaucracy, before consumer choice carried all before it, can only be translated into the infrastructure of charity and PR, where we learn what happens over a few weeks during a TV show and then forget about it. A “permanent” network of Ministry of Food shops – pop-ups that taught cooking skills and had a mostly voluntary staff – were set up in the north of England in Bradford, Leeds, Newcastle and Rotherham, though the latter was forced to temporarily close following health and safety concerns in June 2013, reopening in September 2014.

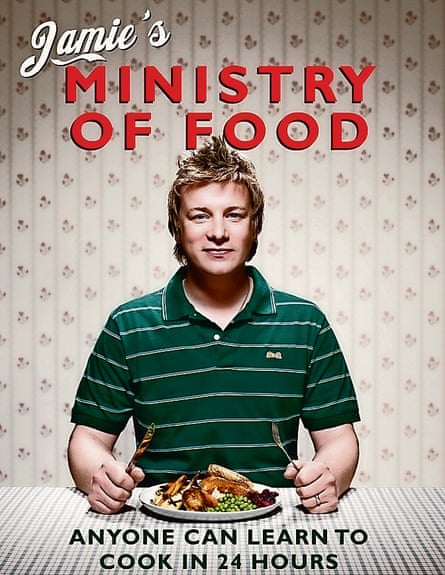

Much more influential than this up by your bootstraps attempt to do a TV/charity version of the welfare state was the ministry’s aesthetics. On the cover of the tie-in cookbook, Oliver sits at a table laid with a 1940s utility tablecloth in front of some bleakly cute postwar wallpaper, and “MINISTRY OF FOOD” is declared in that same derivative of Gill Sans typeface used on the Keep Calm and Carry On poster. This is familiar territory. There is a whole micro-industry of austerity nostalgia aimed straight at the stomach. There is Oliver’s own chain of Jamie’s restaurants, where you can order pork scratchings for £4 (they come with a side of English mustard) and enjoy neo-Victorian toilets. Beyond Oliver’s empire, middle-class operations such as the caterers Peyton and Byrne combine the sort of retro food common across the western world (lots of cupcakes) with elaborate versions of simple English grub including sausage and mash. Some of the interiors of their cafes (such as the one in Heal’s on Tottenham Court Road in central London) were designed by architects FAT in a pop spin on the faintly lavatorial institutional design common to the surviving fragments of genuine 1940s Britain that can still be found scattered around the UK – pie and mash shops in Deptford in south-east London, ice-cream parlours in Worthing in Sussex, Glasgow’s dingier pubs, all featuring lots of wipe-clean tiles.

Other versions of this are more luxurious, such as Dinner, where Heston Blumenthal provides typically quirky English food as part of the attractions of One Hyde Park, the most expensive housing development on Earth. Something similar is offered at Canteen, which has branches in London’s Royal Festival Hall, Canary Wharf and – after its scorched-earth gentrification courtesy of the Corporation of London and Norman Foster – Spitalfields Market. Canteen serves “Great British Food”, “beers, ciders and perrys [that] represent our country’s brewing history” and cocktails that are “British-led”. The interior design is clearly part of the appeal, offering a strange, luxurious version of a works canteen, with benches, trays and sans serif signs that aim to be both modernist and nostalgic. It presents the incongruous spectacle of the very comfortable eating and imagining themselves in the dining hall of a branch of Tyrrell & Green circa 1960. Still more bizarre is Albion, a greengrocer for oligarchs, selling traditional English produce to the denizens of Neo Bankside, the Richard Rogers-designed towers alongside Tate Modern. Built into the ground floor of one of the towers, it sells its unpretentious fruit and veg next to posters advertising flats that start at the knock-down price of £2m.

Closer to reality as lived by most people is a mobile app called the Ration Book. On its website, it gives you a crash course on rationing, when the government made sure that in the face of shortage and blockade the population could still get “life’s essentials” in the form of the famous book, with its stamps to get X amount of dried egg, flour, pollock and Spam. It is an app that aggregates discounts on various brands via voucher codes for those facing the “crunch” – the people the unfortunate Ed Miliband tried to reach out to as the “squeezed middle”. The website states: “Our team of ‘Ministers’ broker the best deals with the biggest brands, to give you the best value.” Is there any better way of describing the UK in the second decade of the 21st century than as the sort of country that produces apps to simulate state rationing of basic goods, simply to shave a little bit off the price of high street brands?

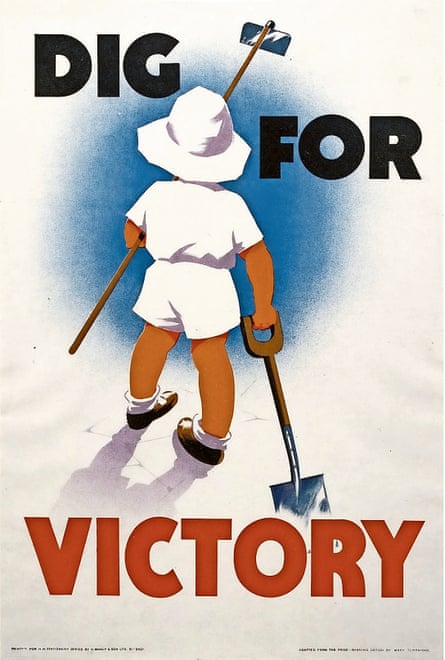

This food-based austerity nostalgia is one way in which people’s peculiar longing for the 1940s is conveyed; much more can be found in music and design. Walk into the shops at the Royal Festival Hall or the Imperial War Museum in London, and you will find an avalanche of it. Posters from the 1940s, toys and trinkets, none of them later than around 1965, have been resurrected from the dustbin of history and laid out for you to buy, along with austerity cookbooks, the Design series of books on pre-1960s “iconic” graphic artists such as Abram Games, David Gentleman and Eric Ravilious, plus a whole cornucopia of Keep Calm-related accoutrements. A particularly established example is the use of the 1930s Penguin book covers as a logo for all manner of goods, deliberately calling to mind Penguin’s mid-century role as a substantially educative publisher. Then there are all those prints of modernist buildings, ready for Londoners to frame and place in their ex-council flats in zone 2 or 3: reduced, stark blow-ups of the outlines of modernist architecture, whether demolished (the Trinity Square car park in Gateshead seen in Get Carter) or protected (London’s National Theatre). The plate-making company, People Will Always Need Plates, has made a name for itself with its towels, mugs, plates and badges emblazoned with various British modernist buildings from the 1930s to the 1960s, elegantly redrawn in a bold, schematic form that sidesteps the often rather shabby reality of the buildings. By recreating the image of the historically untainted building, it manages to precisely reverse the original modernist ethos. If for Adolf Loos and generations of modernist architects ornament was crime, here modernist buildings are made into ornaments. Still, the choice of buildings is politically interesting. Blocks of 1930s collective housing, 1960s council flats, interwar London Underground stations – exactly the sort of architectural projects now considered obsolete in favour of retail and property speculation.

Many of the buildings immortalised in these plates have been the subject of direct transfers of assets from the public sector into the private. The reclamation of postwar modernist architecture by the intelligentsia has been a contributory factor in the privatisation of social housing. An early instance of this was the sell-off of Keeling House, Denys Lasdun’s east London “Cluster Block”, to a private developer, who promptly marketed the flats to creatives. A series of gentrifications of modernist social housing followed, from the Brunswick Centre in Bloomsbury (turned from a rotting brutalist megastructure into the home of one of the largest branches of Waitrose in London), to Park Hill, an architecturally extraordinary council estate in Sheffield, given away free to the Mancunian developer Urban Splash, whose own favouring of “compact” flats has long been an example of austerity sold as luxury – although after the boom, its privatisation scheme had to be bailed out by millions of pounds in public money. Another favourite on mugs and tea towels is Balfron Tower, a council tower block about to be sold to wealthy investors for its iconic quality. It is here, where the rage for 21st-century austerity chic meets the results of austerity as practised in the 1940s and 1950s, that a mildly creepy fad spills over into much darker territory. In aiding the sell-off of one of the greatest achievements of that era – the housing built by a universal welfare state – the revival of austerity chic is the literal destruction of the thing it claims to love.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion