When did pop first show that it had the capacity to feel bad? Not bad in the sense of feeling blue or worried or cross or cray-zee, or bothered by intimations of existential dread, but bad in the sense of feeling disturbed. That pop, rock, soul or whatever had the potential to take both hands off the banisters and let itself fall backwards without thought into abysmal, chaotic feeling. When did rock first show signs that it had the power to express what we might now call, for want of a better expression, pathology?

My first encounter with extreme feeling in pop music came a couple of years before I was capable of registering any kind of extreme feeling myself. In 1971, Janis Joplin was the sound of approaching anguish for my generation of 11-year-olds. Her sandpaper howls were for us, I suppose, what we thought of when we thought of the existential scream of nature, as we often did: an auditory update of Edvard Munch for the post-hippy generation. When she let rip, the world formed its mouth into an O and put its hands up to the sides of its face.

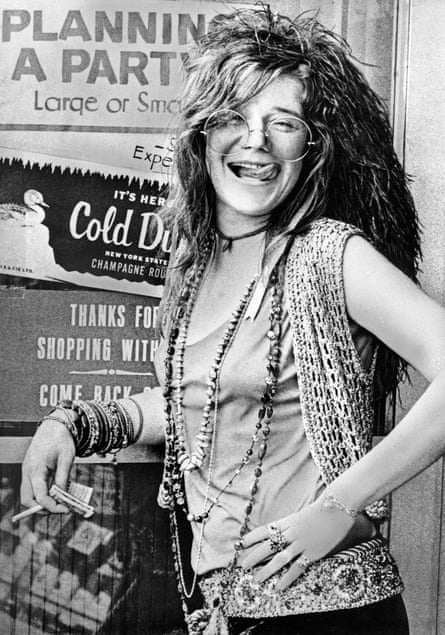

But what did we know of her really? Very little. I remember registering at the time (probably from advertising copy, poster art and LP sleeves) her vivid personal iconography: round, tinted specs, feather boas in her hair and a hungry grin that opened her face to the sky. I also think I acquired the knowledge that she was Texan, that she was a roustabout and that she had expired only recently, as part of the same hippy decimation that had disposed of Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison, all of them victims of excess of one kind or another. Had she lived, she would have been 75 this month.

These events had qualified as real news at the time and had been reported in newspapers and on broadcast media, up to a point. But the reports were not followed up, as far as I was aware, with extended media inquests or compassionate reflection in wider society. It was just news. It was what had happened. I certainly did not tut moralistically over it, but at the same time I was not entirely sure, at the age of 11, about how to think about such things. I felt nervous about them. I didn’t know what heroin was, and I hoped I never had to take it.

I thought of her as an unbridled force and one whose output was fuelled by unhappiness. You couldn’t sound like that and be happy – and nor could you sound like that if you felt at ease within the architecture of the world you had been given: in her case, presumably, the world of strictured white social conformity in the postwar era. A person who sounded like this represented a challenge to your own sense of ease in the world.

The Joplin song you heard emanating most often from the bedroom doors of your friends’ elder siblings, and very occasionally from the radio, was her version of Erma Franklin’s defiant minor soul hit Piece of My Heart, a not wholly unsubtle genre piece penned by jobbing writer/producer Jerry Ragovoy. Franklin’s original 1967 Piece of My Heart is a hymn to strong-willed, if slightly irritable, stoic self-possession in love – it’s a little glum, but it is also resilient.

Joplin’s version, from the following year, takes another road. While her gang of accomplices, Big Brother & the Holding Company, slashes psychedelic weeds out of her path in a far-from-deft rock pastiche of soul instrumental style, Joplin drives a bulldozer through the sentiments expressed by the song. She literally screams it into subordination, beginning the confrontation with the sergeant-majorish bawl to attention, “Co-o-ome on, come on, COME ON, co-o-o-ome on!” as if ordering reluctant listeners to assume the brace position.

What follows is a sort of musical description of bipolarity expressed in the form of extreme dynamic peaking and troughing: LOUD-soft-LOUD, it goes. LOUD-soft-LOUD-LOUDER-LOUDER STILL-soft again … SCREAM-whimper-SCREAM-whimper-SCREAM-SCREAM LOUDER-whimper …

It was one of the features of the relatively uncompressed rock music of the late 60s that you could do this and get away with it provided you set about your work “with soul”. And as a demonstration of unbridled Texas lung power, Piece of My Heart could hardly be bettered. But to pull it off – and I use the expression advisedly; Joplin is circus-theatrical in her display, as if attempting some daredevil stunt – such a performance entails the pulverisation of nuance. It is as if, in Joplin’s take on it, the composition has no expressive value of its own and its sole function as a structure is to serve as a vehicle for the overpowering private anguish – and oomph – of the singer singing it. Joplin does not sing the song; the song sings Joplin, as if what’s inside the singer is all that counts, and never mind what’s inside the song.

This is an edited extract from Nick Coleman’s book Voices: How a Great Singer Can Change Your Life, published by Jonathan Cape on 25 January (£18.99 rrp). To order a copy for £16.14 with free UK p&p, go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion