Peter Frampton recalls with stinging clarity the moment in 1976 when he realized his career was about to take a perilous turn. “I realized that instead of the front row being a mixture of 50-50, male and female, in the audience, it was all females at the front and the guys are pissed off at the back,” he said. “The guys would jeer at me.”

In that moment, Frampton was downgraded from a respected musician to a disposable teen idol. His credibility was being questioned at a time when the standards for such things in music were set in stone, with particular scorn directed at any rock star who was swooned over by teenage girls. Worse, his sales of over 14m copies of the double album Frampton Comes Alive, a world record at the time, set expectations impossibly high for his future. “The success was just so enormous,” he said. “I’m sure it affected me mentally.”

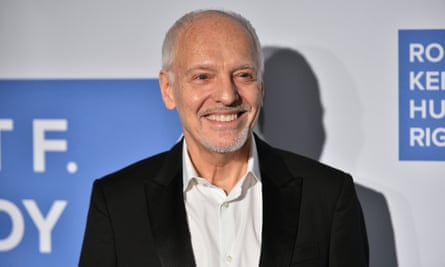

In fact, it set in motion a perfect storm of factors that turned the commercial peak of Frampton’s career into a case-study in rock stardom gone wrong. Now, the musician, aided by writer Alan Light, has detailed all of those issues in a bracing new memoir titled for one of his best-known songs, Do You Feel Like I Do? It’s a question few are likely to answer in the affirmative given the series of rip-offs, sketchy management deals and unfortunate choices Frampton made back then. At the same time, the book highlights his many creative achievements, from his days as a guitar prodigy, to his time fronting the hit band the Herd, to his formation with Steve Marriott of one of the world’s first super groups, Humble Pie, to his promising early solo work. More, the book shows how Frampton eventually managed to re-figure his career, putting the focus back on his unique approach to the guitar. “I knew I would make it back,” Frampton said in his characteristically upbeat tone. “It just took a lot longer than I thought.”

He credits that belief in himself – a trait which is currently sustaining him through a highly publicized degenerative muscle disease diagnosis – to his stable and loving upbringing. It helped that he shared a flair for creativity with his father, who served as the head art teacher at the school he attended. It was there Frampton met one Dave Jones – the future David Bowie – who was taking a class taught by his father. “Everything my dad taught, Dave lapped up,” Frampton said. “Dad recognized his brilliance in art. And we became friends.”

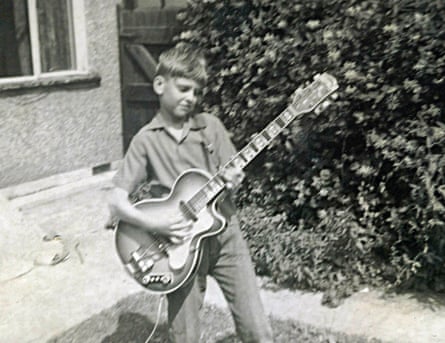

His father’s taste even wound up affecting Frampton’s approach to the guitar. As a kid, he was drawn to the barreling instrumental work of the Shadows, but his dad introduced him to the fleet work of Django Reinhardt as well. “That led me to George Benson and Kenny Burrell and all these jazz guys,” he said.

The influence of such artists gave Frampton a different template to draw from than most of the British guitarists of his day who obsessed solely on the blues. “Every guitarist wanted to play like Eric Clapton,” said Frampton. “Of course, I love Clapton’s playing but I thought if I just do that, I’m going to be another copyist. I wanted a combination of jazz and blues and heavy rock.”

That combination inspired Frampton to create a unique style in which he often plays around the melody rather than hitting it straight on. Unfortunately, his first successful band, the pop-oriented the Herd, offered limited chances to develop his skills. Instead, the media focused on Frampton’s uncommonly pretty looks, setting off what became a lifetime issue for him. The music papers named him “The Face of 1968”. Still, his fellow musicians recognized the elevated power of his playing. Steve Marriott, of the hugely popular Small Faces, approached him about joining that band, though the other members felt they were fine as they were. It was during this time that Frampton got his first hint at how difficult and self-destructive Marriott could be. One time when he was hanging out with the Small Faces, their agent received a call asking if they would like to be the opening act for Jimi Hendrix’s first American tour. “Steve said, ‘Fuck that! We’re not opening for anybody,’” Frampton recalled. “I’ll never forget Ronnie [Lane’s] face. It was despair.”

Frampton believes that had the Small Faces toured the US at that time they “would have been a second Who”. Instead, Marriott ditched them and started jamming with Frampton, along with the ex-Spooky Tooth bassist Greg Ridley and drummer Jerry Shirley, the powerhouse foursome that became Humble Pie. In 1969, they issued a brilliant debut, As Safe as Yesterday Is, but the album and its follow-up had limited distribution. Humble Pie’s early music was wildly creative but it lacked focus until producer Glyn Johns whipped the band into shape for their impressive fourth album, Rock On. He pushed them towards harder sounds, an approach intensified by their fifth release, the live Rockin’ the Fillmore, released in the fall of 71. The power of that album set the band up for a huge breakthrough in America but, to everyone’s shock, Frampton chose that moment to split. “I thought, if I don’t leave now, I won’t be able to,” Frampton said. “I’ll get drawn into it.”

The other members thought he was crazy, but he considered the band’s harder direction too limiting. Another factor was Marriott’s difficult side. “We were like brothers,” Frampton said, “but he could really suck the oxygen out of a room. I didn’t need to deal with that any more.”

As big a leap as the move to a solo career was, Humble Pie’s label, A&M, supported the decision, as did their powerful manager, Dee Anthony. Still, going it alone meant Frampton would have to serve as sole lead singer, a role he knew wasn’t his forte. “I was nervous, especially after coming from a band with one of the all-time greatest rock singers, Steve Marriott,” Frampton said. “I was jumping off the high wire.”

Luckily for him, A&M provided him a wide enough net to float three solo albums that didn’t sell well. His fourth, Frampton, began to turn things around. But no one anticipated the blockbuster breakout of Comes Alive the next year. Thrilling as that was, Frampton’s looks once again upstaged his talent. This time the issue became so overwhelming, the guitarist found himself thinking often of a quote from Sir Laurence Olivier about his wife, the actor Vivien Leigh. “He once said in an interview, ‘it’s so upsetting that she is always told how beautiful she is. She’s a phenomenal actress,’” Frampton recalls. “I absolutely understand that.”

It didn’t help that Rolling Stone featured him as a shirtless object of teen fantasy on their cover. At the same time, he had to endure intense pressure to follow up a smash. The rushed result, I’m In You, was excoriated by critics. As the coup de grace, Frampton agreed to star on an epically awful film version of Sgt Pepper. Though wary about the project, he went along partly because his manager told him that Paul McCartney would be in it – a bald-faced lie. Of the film, Frampton writes, “there was barely a script. It just said, ‘Walk in here, someone will yell “playback” and then you lip-sync.’ Everyone thought we were too big to fail.”

When the film, in fact, failed spectacularly, Frampton was too doped up on morphine to notice. Doctors prescribed the drug to him to help him recover from a near fatal car accident he just suffered in the Bahamas. Then came a new horror: his manager had been ripping him off all along, resulting in his total bankruptcy. “I had less than nothing,” said Frampton. “I owed hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

While he now takes responsibility for putting his trust in people who didn’t deserve it, Frampton asserts that manager Dee Anthony (who died in 2009), had been telling people not to discuss finances with him. “I was kept away from those things,” he said. “I was kept high. If I needed weed, he made sure I had weed. If I needed cocaine, he made sure I had cocaine. He didn’t want me thinking about what was going on. It was criminal. I could have put him in jail.”

In fact, Frampton says Anthony did have criminal connections. Early in his solo career, the manager introduced him to his associate Joey Pagano, a known mafia don. “He was saying to me, ‘look how powerful I am,’” Frampton said.

Even after he fired Anthony, the guitarist struggled financially and creatively. At a low point, he got a puzzling call from Pete Townshend who told him he was leaving the Who and wanted to know if he would take his place. “It was the most bizarre thing I ever heard,” Frampton said, with a laugh. “Three men couldn’t fill his shoes!”

Consequently, he first turned the offer down. Some days later, however, Frampton’s sad financial state spurred him to call back, at which point Townshend acted like the whole thing never happened. Things kept going in a bad direction until 1987 when Frampton’s old pal Bowie called to ask if he would be a guest player on the hugely popular Glass Spider world tour. The result energized his spirit. As a result, Frampton’s next solo album, When All the Pieces Fit, in 1989, was the first work he was proud of in years. In the time since, the guitarist has continued to tour and put out albums up through 2018’s All Blues. Last year, he launched a highly successful “farewell” tour necessitated by the advance of his disease, known as inclusion-body myositis.

These days, Frampton says he feels largely well. He’s still able to play guitar at home. And he just cut a new song with members of the Doobie Brothers. Regarding his current ailment, Frampton takes a philosophical view. “It’s life-changing, not life-ending,” he said. “Is it sad? Yeah. But I have to put it in perspective. I’m here. And I’m very pleased with how everything in my life turned out.”

Do You Feel Like I Do? is released on 20 October