We all know what Philip Larkin reckoned your mum and dad do to you, but rarely do we have the opportunity to see the process in action as clearly as in the compelling Channel 4 documentary Trophy Kids.

It was the story of four talented children withdrawn by their parents from anything approaching normal life in order to be hot-housed to stardom in their chosen sports, and it added an extra dimension to some of the action over the weekend – Jenson Button in the grand prix, Andy Murray winning in Miami, Wayne Rooney scoring two goals for England.

All three of them were talented prepubescents not long ago and in the light of the Trophy Kids, who seemed to be suffering a comprehensive Larkining up from their folks, you could not help wondering if Jenson, Andy, and Wayne had to go through something similar to get where they are. You would hope not.

It is difficult to imagine Judy Murray, for instance, being as ferocious as the tennis dad in Trophy Kids; yet when Murray threw away a point in the deciding set against Juan Monaco on Saturday night, the camera caught her in the stand, thin-lipped in disappointment. There was even a touch of anger.

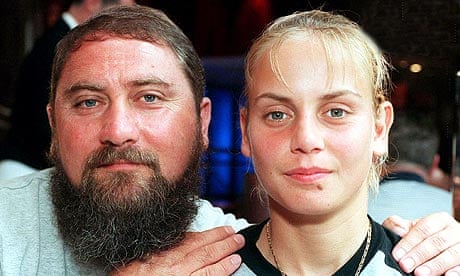

At least she was not stalking around muttering oaths and getting into rows with officials, like Roger Silva in Trophy Kids who saw his daughter, Eden, throw away a lead to lose in the quarter-finals of the world under-12 tennis championships in Florida. Had no one told him that quarter-finals are what we Brits do (Andy excepted)?

You could understand Roger being a trifle piqued. He had given up a high-earning job to take Eden to see the best coaches, physios and even racket stringers around the world. He had gone through £120,000 of his dwindling savings in 18 months and looked to have blown his last 30 quid on the bottle of Glenmorangie from which he poured an understandably large measure as he totted up the damage. I only hope they gave him a few bob for the product placement.

Andy Spooner and his son, Billy "the Iceman" Spooner, also tasted defeat in America, in the world under-11 golf championship, where Andy caddied and father and son wore identical Bermuda shorts. I could not decide which I found spookier, calling a nine-year-old "The Iceman" or introducing him to dodgy leisure wear at such a young age.

At one point, Billy missed a putt and his dad said: "Billy, what are you doing? Your career's on the line." (Can a nine-year-old be said to have a career? Judy Garland and Macaulay Culkin could, I suppose, and we all know how well that turned out.)

To parents like your columnist, who had used his own body weight in Blu-tack by the time his kids reached puberty, attaching every bit of daubing they brought home from school to the fridge, and applauded every second place in the egg-and-spoon race as if it were Olympic gold, this was strange and unfamiliar territory. In fairness, Andy Spooner seemed a decent chap, who acknowledged the strain the golf was putting on his relationship with the Iceman.

Allowances must also be made for selective editing. Clearly, a documentary about pushy parents will favour sequences in which kids are being Larkined up over ones in which they are being given a consoling hug or a bowl of Coco Pops. That can be the only explanation for the real horror of the piece, Ian Spurling, father of 11-year-old Lee "the Wolf" Spurling — the new Tiger Woods, according to his dad. Lee had also been taken out of school, in order to concentrate on his daily golf practice.

Now he rarely leaves the house, except to go to the golf course with his parents or to the Ferrari garage so Ian can show him the fancy cars he will be able to afford when he conquers the world. The Wolf broke down and cried when asked about friends, of whom he seemed to have few: "They keep accusin' me dad of doing it for the money and it's doin' me head in," he said, but as his dad never shut up about cars, yachts and fortunes, you could see how they might have formed that view.

The parents, of course, believe they are doing the best for their children. They see themselves as Earl Woods or Judy Murray, rather than Damir Dokic. It is a thin dividing line, though, and I am not sure that inviting the cameras to film your kids' childhood is the way to stay on the right side.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion