When David Haye, from the planet Earth, fights Nikolai Valuev, a Russian from the recesses of his worst nightmare, in Nuremberg on Saturday night, the temptation to regard the disparity in their sizes as an amusing curiosity will be tempered by concern and awe. Friends and family might even fear for Haye's health.

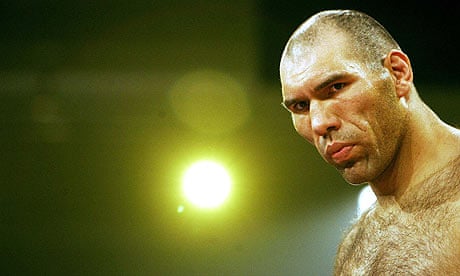

It is inevitable that every time Valuev fights – or enters a room, for that matter – he invites discussion about his dimensions, as if he were from a catalogue of giant people. Valuev insists he is not a physical freak suffering from a pituitary gland disorder; he is a genetic throwback, the son of parents who each are 5ft 5in tall, with a Tatar ancestor of mountainous proportions.

More pertinently, Valuev is a professional boxer, a recognised world champion of some competence who has won 50 of his 52 contests, dating back to 1993. So he poses not just a boxing conundrum for opponents he often dwarfs by a foot and several stones but, on the face of it, a serious physical threat.

However, the physiology and biomechanics of boxing are so extraordinarily complicated that Mike Tyson (5ft 11in, 15st 7lb at his peak) was correct to point out this week that a fighter of 4ft 6in could seriously inconvenience a much bigger opponent if he were to land a blow in the right place and at the right time.

Danger in boxing is a shared commodity, as Dr Ashwin Patel, a ringside doctor for the British Boxing Board of Control in hundreds of fights over 23 years, explains.

"In boxing there are two injuries we are always concerned about," Dr Patel says. "One is damage to the brain, the other is exhaustion and fatigue. If you have more weight than your opponent, it does not mean you are more or less likely to have a brain injury, but certain bigger individuals will get [more] tired if they are taken the distance. That is when exhaustion becomes a factor. It ultimately does not matter what weight you are, however. It is your physical condition that is more important.

"If you are very heavy, you are straining your heart but, if Valuev has been 23 stones for the last several years, then his heart is conditioned to take that load. However, he will get exhausted sooner by a clever boxer who can make him run around the ring."

While he will go after Valuev amidships, the chin remains the main object of derision for Haye; the problem is connecting with full force on a target that will seem as distant as Mount Everest, and just as hard. His power in throwing punches a good six to nine inches above his own shoulders will be dissipated considerably. The trick is to bring Valuev's head down to his own fists, and that is why he will work the body.

"The Russian will have a heavier punch but, if Haye is clever, he can exploit Valuev's weaknesses," Patel says. "In all of us, there are certain areas of the body where the bone is closer to the skin. Especially I am talking about the lower part of the rib cage. There is very little fat there. Blows there do hurt.

"If you are tall you have to hit down to hit the rib cage, and you expose your head in so doing. If you are short and trying to hit the ribs of a much taller man, your punches are going straight, so they have more force."

The rise and rise of boxing's biggest battalions over the past century is a societal as well as sporting narrative.

John L Sullivan, the first universally recognised gloved heavyweight champion, from 1885 to 1892, was a stumpy 5ft 10½in bar-room bruiser who weighed just over 14 stones. He was considered a big man for his time. The Cornish-born Bob Fitzsimmons, champion from 1897 to 1899, stood a spindly 5ft 11½in and weighed just 12st.

Diet and conditioning grew the breed steadily over the next 50 years, with occasional "freaks", such as Jess Willard, who was 17st and 6ft 6½in during the first world war, and the tragic Mob dupe Primo Carnera (6ft 5½in, 19st 2lb), who ruled for just a year in the Thirties.

If Henry Cooper were boxing today, it is inconceivable he would be allowed anywhere near Valuev, or the awesome Klitschko brothers. The 6ft 2in Cooper rarely weighed more than 13st 7lb – often much lighter. He would have to spot Valuev an off-the-beer Ricky Hatton. Yet Cooper was able to floor Muhammad Ali, who weighed 14st 7lb, when they fought at Wembley in 1963. This was Tyson's law in action.

Valuev, the current WBA champion, is 7ft tall, will weigh about 23st on the night and has an 84-inch reach, 10 inches longer than Haye's. He has never been wobbled. But he is not a concussive one-punch knockout artist. Only eight of his opponents have been counted out, compared to the 26 stopped through the intervention of the referee, although a good many of those who hit the canvas would gladly have stayed down for the full count.

Among those was the New Zealander Tone Fiso, who, at 324lb, is the only opponent to outweigh Valuev (by 4lb), and was left staring at the ceiling inside a round when they met in 2000.

When Valuev fought in Prague the previous year, the referee (in his only professional engagement) was so concerned for the safety of Valuev's 6ft 5½in, 16st 4lb German opponent, Andreas Sidon, he gave him two standing eight counts in the first round for no legitimate reason. When he then attempted to abandon the fight, the puzzled boxers carried on without him for another five rounds. The farcical bout, later declared a no-contest, underlined the circus element of Valuev's bizarre career.

The lugubrious Russian, then, whose cranial shelf casts a shadow of its own, intimidates as much by his presence and physicality as unstoppable power. He is easy to fear, impossible to ignore.

Haye's plan is a simple one: hit hard and straight to the body – and move. Or be moved.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion