1) The essence of Boon

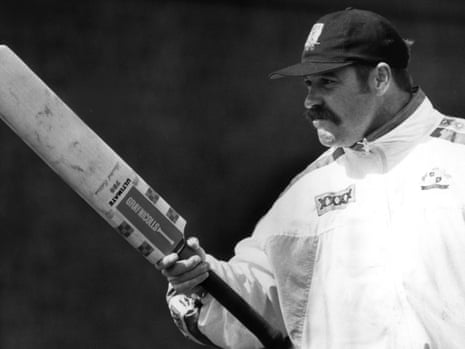

Along with his long-time captain and batting ally Allan Border, David Clarence Boon was the tough, unbreakable chain that linked the hirsute, macho-man glory years of the Chappell era to the decades of prosperity that followed Australian cricket’s breakthrough series victory in the Caribbean in 1995. In between times, it was often due to the stoic, unfussy efforts of Boon that Australia were able to lift themselves off the canvas in the early years of Border’s era.

There is something about the legend surrounding Boonie that evokes nostalgia from even the most casual cricket fan. You’d be lying not to acknowledge the role that a certain famous drinking session played in that image, but focusing on Boon’s VB-sinking prowess and the accompanying marketing machine obscures the more meaningful ways in which he helped shaped the course of Australian cricket as a durable, flint-hard team man and an underrated batting force.

Boon never really played with fluency or offered eye-catching stokes, but the fact that he remains such an intrinsic element of his country’s cricket lore speaks of the gradual disappearance of his own masculine brand of Australianness.

In that sense Boon is now frozen forever in time, readjusting his protector, scratching at the pitch with his bat or standing silently at short leg like a faithful doberman, waiting to pounce on an inside edge. Thumped in the ribs or arms by West Indian quicks (or Wasim Akram) as he often was, Boon would just clench his teeth and refuse to rub the sore spot. It was like he took pleasure in not displaying pain.

Still, at various points during the late 80s and early 90s Boon was considered by some to be the best batsman in the world. His home crowds saw the best of him too, with 15 of his centuries coming in Australia.

In the Test arena he was unerringly consistent in the most literal sense, averaging 43.60 in the first innings and 43.74 in the second. Runs often came when they were most glaringly required and 15 of his 21 Test centuries were scored when the series result had yet to be decided. A nagging accumulator who sweated on the short ball with a brutal late cut, Boon’s batting succeeded on the basis of application and crease occupation rather than dominance or flair. Only twice did he clear the pickets in the Test arena, a measure of self-control that served Australia well in times of austerity and against the might of the West Indies attacks Boon encountered throughout his career.

Boon became only the second player after his captain Border to win 100 Test caps for his country and his efforts at the top of the order in 181 one-day internationals were probably underrated next to the flashier offerings of his contemporaries. It was Boon’s calm and collected 75 that clinched the 1987 World Cup for Australia. His average of 37.04 in ODIs might have been a little higher had he not honoured a pact with the stodgier Geoff Marsh that Boon play all the shots while his opening partner occupied the crease.

2) Boon the team-mate

Border once labeled him “my rock of Gibraltar” and if you were picking an all-time XI of Australia’s greatest team-mates, Boon would be close to the top of the list. In a time of great need, Boon’s emergence on the international arena lent Australia backbone when Border had seemed to be fighting a one-man battle.

Boon never complained when he was shuffled around the batting order as the needs of the team dictated and his reaction to being dropped early in his career was merely to force his way back immediately through sheer weight of runs and hard work. No one pushed themselves harder in the nets or on their running between the wickets than Boon, a factor often overlooked on account of his, shall we say, stocky physique. Boon’s loyalty bred similar traits in others and without his understated presence as Border’s right-hand man, the captain would have been under much more pressure.

Key to his position as the Australian side’s heart and soul was Boon’s responsibility to deliver of the team song, Under the Southern Cross, after each win. Boon imbued this ritual with the gravitas that further entrenched it as a rite of passage in Australian dressing rooms. No Aussie triumph was complete without his well-timed ascent to the top of a physio’s bench or card table to belt out the verse.

Having a quiet word with Boon following his own retirement, Border said to his trusted offside: “We’ve been doing this for a while, but now it’ll be up to you to never, ever let these younger blokes know what it’s like to get their backsides kicked week-in, week-out.” To call Boon a “team man” is actually to undersell his value. Richie Benaud put it best: Boon was actually “one who made the team what it was.”

3) Boon against the West Indies

Appropriately enough given his long-running battle with various formations of their pace brigades, Boon’s Test career started with a baptism of fire against Clive Lloyd’s 1984-85 West Indies side. Having also hit Lloyd’s men for a century in the Prime Minister’s XI game that summer, Boon acquitted himself admirably on his Brisbane debut with a half-century in the second innings.

Replacing Graham Yallop for that first game, Boon was unceremoniously tossed his baggy green cap by ACB staffer Ron Steiner and thrown into the deep end. Knock-kneed with nerves in his first innings, Boon settled better in the second but Malcolm Marshall gave the debutant some stern instructions: “Boonie, I know this is your first Test match, but are you going to do the right thing and get out or do I have to come around the wicket and kill you?”

Inspiring even less confidence in Boon upon his appearance at the crease, Australian tailender Rodney Hogg quipped: “This is the perfect opportunity to start your career with a not out because I don’t think I’m going to hang around too long.” The Aussies were thrashed by eight wickets and skipper Kim Hughes famously quit the top job in tears in the aftermath of the defeat.

The Caribbean barrage never let up. The 1988-89 series was the first time Australian crowds got a close-up glimpse of Curtly Ambrose. The experience was a little more bracing for Boon and his batting cohorts, but the Tasmanian still carved out 397 runs for the series to lead all Australian batsmen. His innings of 149 at Sydney underpinned a rare Australian win, the only one of the series and a minor turning point in the lopsided rivalry between the two sides. Of that series (one in which Geoff Lawson had his jaw shattered by Ambrose) Boon would later noted: “Happiness and joy are not the first adjectives which springs to mind when one thinks of facing Curtly Ambrose.”

The spiteful 1991 Caribbean tour ended up an unhappy one for Australia and for Boon, who could only manage 266 runs for the series, but an undefeated century in the drawn Jamaica Test typified his bravery in the firing line of the West Indies attack. Struck on the face by Patrick Patterson with a blow that later required stitches (no anesthetic though, obviously), Boon just ploughed on in what he’d later describe as one of his most satisfying innings.

The 1992-93 series saw Boon at his best with 490 runs at 61.25 and the pick of his innings was a counter-punching 111 in combination with Mark Waugh during the first Test at the Gabba. It was the second and last of two hard-fought tons against a bowling attack with whom he probably shared the honours in the end. Ironically, when Australia finally usurped the West Indies on the 1995 tour, Boon’s run of form was uncharacteristically modest and precipitated his retirement from the game less than 12 months later. Finishing off in the same fighting spirit as he’d started, Boon dueled memorably with a rampant Courtney Walsh and no one begrudged him a share of the spoils against a side for whom he’d long provided stout opposition.

4) Ashes Boon

Though he’d eventually take English attacks for seven Test centuries and share in the celebrations of four successful Ashes campaigns, English fans might have had reason to assume they’d never see Boon again following his modest returns of the 1985 Ashes tour. His four Tests reaped just 124 runs at 17.71 but just as Australia’s stocks gradually rose through the latter half of the 80s, so too did Boon’s.

He was an underrated batting bulwark in the 1989 tour upset, failing only in the ability to push to three figures while accumulating 442 runs at 55.25 and knocking off the winning runs that sent the Australian team balcony into series-winning raptures at Old Trafford. The 1990-91 home series that followed was even more profitable: 530 runs at 75.71 bettered most of Australia’s specialist batsmen by 200 or more.

Though he’d hoped to push through until 1997, the ’93 tour of England was Boon’s last and his English love affair reached its peak with 555 runs and a Bradmanesque run of three centuries in consecutive Tests at Lord’s, Trent Bridge and Headingley. In the slaughter at Lord’s, Boon was unbeaten on 164 when Border finally declared Australia’s only innings.

Boon’s success on English shores is probably indicative of the esteem in which he held the Ashes tour, one he considered “the ultimate for an Australian cricketer”. Respectful of Ashes history and those who’d preceded him, he saved some of his very best batting for English attacks.

5) Boonie the short leg

Was there a braver or better short leg fieldsman than Boon? Did any other player make you shake your head so frequently that a man placed so close to the bat could react so sharply to balls flying off inside edges and even the middle of the bat? Most certainly, Boon’s physique seemed at odds with his agility in the field. “How does this guy move so quickly?” you’d ask yourself.

Boon turned the short leg fielding position from one of speculation and hopefulness into a refined attacking weapon. His impact on batsmen should not be underestimated; such was the frequency of their dismissal at his hands. He’d snaffle 99 catches by the end of his Test career, none more famous or remarkable than the one-handed dive to dismiss Devon Malcolm and hand Shane Warne a hat-trick during the Boxing Day Test of 1994.

Other examples are many and varied. At the MCG again in 1993, Boon snared Hansie Cronje from silly point in a near mirror image of the hat-trick catch, this time diving low to his right to complete the one-handed take. Set slightly further back at short mid-wicket with Steve Waugh bowling to Brian Lara on Australia’s victorious 1995 Caribbean tour, Boon reeled in a sensational dive and one-handed catch. In times of need, most famously the 1992 World Cup in which the injured Ian Healy couldn’t be replaced from outside the selected squad, Boon even stepped up to take on wicket-keeping duties.

No player better represented the possibilities of close-in fielding and the attacking dimension that can be added to a bowling plan by the fusion of courage, razor-sharp reflexes and focused attention that Boon brought to his fielding efforts.

6) Boon the Tasmanian Icon

No player in Australia more obviously carried the hopes of his home state quite like David Boon did from the mid-80s, until Ricky Ponting’s arrival on the international arena a decade later. A batting wunderkind as a teenager, Boon was unique in having been front and centre as Tasmania went from bit-part players in domestic competition to legitimate Sheffield Shield contenders. He simply was Tasmania on the global stage for much of his career, a burden of pressure that never unduly affected Boon’s steady, affable nature, nor the regular flow of runs.

As a 17-year-old, he’d helped fire his state into the final of the 1978-79 Gillette Cup, which they won to no small fanfare at home. In the aftermath of that semi-final win, further hints of Boon’s future mythology could be seen on the pages of the Australian, which carried shots of the underage batsman and his skipper Jack Simmons sinking a post-match beer.

Boon’s biographer Mark Thomas noted that, “in Launceston and the rest of Tasmania, David Boon was everyone’s property,” but an element of the Boon story that’s receded from view over the years is the fact that he almost defected to rival states on a number of occasions. A switch to South Australia for the 1983-84 summer only fell through due to complications with Boon’s day-job in a bank. Then in the wake of Australia’s 1987 World Cup triumph and having been stripped of the Tasmanian captaincy following a drunken tussle with team-mate Glenn Hughes, Boon asked his national team colleague Dean Jones to sound out a potential move to Victoria. The move was only quashed by Victoria’s Ian Redpath, who felt Boon was better off riding out the rough patch in his home state.

Eventually Boon’s impasse with Tasmanian officialdom receded and with the exception of brief interludes (Roger Woolley and Greg Campbell), he remained the jewel in the crown of Tasmanian cricket. Boon also paved the path for others to follow. Fellow Tasmanian and former ABC broadcaster Neville Oliver probably put Boon’s legacy best when he said “the expectations of every Tasmanian were squarely on his shoulders. I don’t think Ricky Ponting will feel anything even vaguely approaching that because of David.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion