It is hard to give fury a form. But the theatre is having a go. In the 1970s the Angry Brigade flour-bombed the Miss World contest and set off explosive devices in Biba and elsewhere. In 2011 an offshoot of the hacktivist group known as Anonymous disrupted Egyptian government sites and replaced the online front page of the Sun with a story announcing the death of someone called Rupert Murdoch. Both these groups were young – the Angry Brigade were student age, one of the hacktivist stars was 15. Both organisations fell outside recognisable political groups. Now the activities of both, partly fictionalised but based on real-life characters and incidents, have been put on stage.

James Graham – still in his early 30s – has rapidly become one of the country’s foremost political dramatists. His lively play about the House of Commons, This House, sped to success at the National in 2012. Earlier this year, in Privacy, Graham moved his gaze away from establishment capers and made a startling interactive drama. He is too young to remember the excited press coverage of the Angry Brigade. Both he and James Grieve, of Paines Plough, who directs, discovered the group with astonishment. Together they make a serious but merry shift at bringing the Brigade’s aims and activities to life. It’s an uneven affair with something of the quality of a first draft, but a promising one.

Four not ultra-bright police people behave as if they were taking part in a plod skit, hands behind their backs, twitching as they try to relax. They are on the trail of the anonymous bombers – the formation of the Met’s bomb squad dates from this investigation – and they tie themselves into a cat’s cradle of complications. The crucial, ingenious pivot of the play, at the moment too deliberately performed to be the comic high point it should be, comes as the crew try to think themselves into an alternative frame of mind. They do it by finding different ways – perching, straddling, swivelling – to sit on a chair. They hang there, some of them upside down. Shortly afterwards, all four, bouncing along to a 70s soundtrack in Grieve’s ebullient production, are playing their prey.

Graham is not alone in being fascinated above all by the character of one of the Angries. Anna Mendlessohn was the epitome of a middle-class British insurgent: the head girl who became a student at Essex when the university was at its revolutionary height. She conducted her own defence, was imprisoned and on release turned to motherhood and poetry. She died of a brain tumour five years ago. Patsy Ferran, who made her stage debut earlier this year as a very funny maid in Blithe Spirit, brings a special quality to the part. She manages to seem both focused and elusive, to persuade you that this woman has it in her to be both poet and activist.

For all their anarchism, the Angries were an entity. The LulzSec hacktivists featured in Teh [sic] Internet Is Serious Business were not: they were dispersed, anonymous and not centrally organised. They were also extremely effective in causing chaos. All this makes it absolutely right of the Royal Court to put on Tim Price’s play as part of their revolution season. The story is mysterious and paradoxical, encapsulating some of the most arresting current phenomena: the person who sits alone talking to unseen hordes; the brilliant student regarded as a pest by his teacher; the way in which the 21st century despises privacy but advocates anonymity.

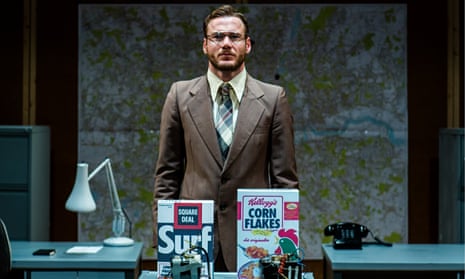

The slipperiness that makes this story fascinating also makes it hard to stage. This should be one of the most disturbing and liberating of plays. It is not. It does convey the freewheeling, catch-all quality of the enterprise. Hamish Pirie’s antic production, set on a grey stage above a brightly coloured ball pond, projects manic excitement, a jumble of the trivial and the significant. It takes in blots of misogyny (“there are no girls on the internet”) and of heartlessness (a suicide raises a chuckle) as well as the beginnings of revolt in Tahrir Square. One young hero is unable to go and have a McFlurry because he has to link up with some Egyptian activists. It makes a good shot at making computerspeak into a dance form, when a series of brackets are mimed as bendy gestures.

Still, the story has been so extensively and intelligently reported that there needs to be a particular reason for dramatising it. No one would expect hard news to be broken, but audiences might look for clarification or vital projection of what they think they already know. Pirie’s production eschews the digital – there is not a screen in sight – and translates the virtual into flesh and fabric. Well-known memes – Grumpy Cat and Socially Awkward Penguin – caper around as if at an uninviting fancy-dress party for tinies. The paradox of such literal representation may be part of Price and Pirie’s point. But I could have done with more stage rage.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion