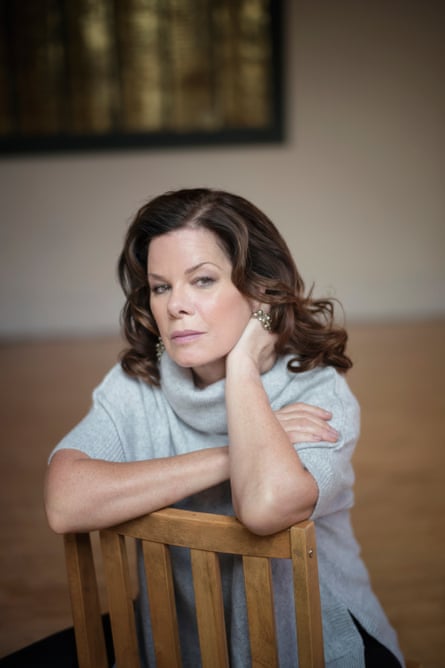

Marcia Gay Harden is a fortnight into rehearsals and having difficulty sleeping due to the lines that are going round and round her head. It’s not that she’s anxious about remembering them, but because they are so troubling. The latest in a long line of leading American actors to sign up for meaty roles on the English stage, she is taking time out from a busy film and TV schedule to do battle with a character she doesn’t yet love, in a play that she sometimes wants “to tear apart with my nails”.

The drama in which she is making her UK stage debut is Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth, and the character is a ravaged Hollywood star holed up with a disgraced gigolo in a small-town hotel, after fleeing the fallout from her comeback movie. Both are addicts who drown their misery in drugs and liquor. “It’s so dark,” says Harden. “The self-degradation that both of them are going through will wake me up in a nightmare.”

One obvious theme is the ruination of age. “The screen’s a very clear mirror,” says her character Alexandra Del Lago, who is in hiding as the Princess Kosmonopolis. “There’s a thing called a close-up. The camera advances and you stand still and your head, your face, is caught in the frame of the picture with a light blazing on it and all your terrible history screams at you while you smile.”

In the 1959 premiere, directed in New York by Elia Kazan, Del Lago was played by Geraldine Page, who was not yet 40 (and only a year older than Paul Newman, who partnered her as the much younger Chance). Harden is 57 and performing, in Jonathan Kent’s Chichester festival theatre production, opposite her 35-year-old compatriot Brian J Smith. “If you think about old Hollywood, Del Lago would have been doing her leading roles during her 20s and 30s and probably would have felt washed up in her late 40s,” she muses.

While conceding that “the issue is of course still pertinent: in Hollywood, where are the roles for older women?”, Harden is adamant that the play has to be more than a whinge about wrinkles and thinning hair. “There is an inevitability in ageing and to think one is going to bypass the effects is immature and shallow. I believe what he’s actually writing about is loss, and that’s a more profound thing to play. The greatest tragedy of humanity is our awareness of our own mortality, and ageing is the clock ticking.” She cites Del Lago’s lament: “I’ve been accused of having a death wish, but I think it’s life that I wish for, terribly, shamelessly, on any terms whatsoever.”

The trap, she believes, is to play Del Lago as an out-and-out monster, though she often appears to be one, and she comes from a line of mid-20th century monsters created for the stage by writers such as Williams and Edward Albee. In Sweet Bird or Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virgina Woolf, they created powerful parts for women, but “I was thinking: in order to be a strong woman, did you have to be a monster at that time?”

Strong women have been a feature of Harden’s career, from the comically steadfast fiancee of Robin Williams’ scatty professor in the sci-fi comedy Flubber (1997) to the tempestuous Lee Krasner, wife of abstract expressionist artist Jackson Pollock, a role that won her a best supporting actress Oscar in 2001 for the biopic Pollock. Most recently, she reaffirmed that strength in the CBS hospital series Code Black, in which she saves life and limb as gung-ho hero Leanne Rorish, and in the Fifty Shades of Grey films, where she makes fleeting appearances as Christian Grey’s adoptive mother.

Dr Grace Trevelyan Grey is an elegant paediatrician who is the only person unafraid of the squillionaire sadist at the centre of EL James’s novel and the movie franchise. Harden carried the persona into her personal Twitter stream, where she cracked jokes about mistaking a nipple clamp for a brooch and thanked her son for leaving a bracelet under the Christmas tree (the accompanying picture showed a string of anal beads).

She was amused when her tweets were “shut down” by the studio. “I ended up getting in a wee bit of trouble for it because they didn’t want to play up the sexual nature – but come on guys, it’s a love story with handcuffs.”

She accepted the role because she was curious about being part of an “event” movie. Although she has worked on prestigious films by such directors as the Coens, Clint Eastwood (Space Cowboys and Mystic River) and Sean Penn (Into the Wild), she says: “I’ve never been at the ‘top top’, where we’re talking millions of dollars and people screaming at you in the street.” (It’s what Alexandra Del Lago describes in Sweet Bird as “the top of the beanstalk, the country of the flesh-hungry, blood-thirsty ogre”.)

“Do I want to live there?” says Harden. “No! I have children so I don’t want to be on top because I’d be travelling all the time, in the gym 24/7, constantly having facial work. So you give up certain things.”

Tongue-in-cheek though she is about Fifty Shades – “everyone is, including EL James” – she defends its message. “I like what it was doing for women who were thinking about their sexuality. It was a little bit of an awakening for women of my own age. It allowed them to be a bit randy and bawdy.”

As such, it fed into her own mission to speak out for “an entire population of women in their 50s who are dumped. They’re typically past their sexual prime. They’ve had children and it’s not about bouncing around in the sack and proving their sexuality, but suddenly they’re alone and the question is glaring: will they ever have sex again? I hope it helped them.”

Harden herself was divorced five years ago from the father of her three children, props master turned documentary director Thaddeus Scheel, whom she married after a whirlwind romance on the set of her 1996 film The Spitfire Grill.

Bemusingly, her brother and her father are also called Thaddeus. Her father was an officer in the US Navy, whose job meant that she had an itinerant childhood, doing the rounds of naval bases from Germany to Japan. In her Oscars acceptance speech for Pollock, she paid tribute to “Dad for teaching me how to soldier through tough situations and Mum for helping me to do it gracefully”.

What sort of tough situation was she imagining? Well, she says, for a start an actor’s life is “300 rejections to every job you get - and some of them you don’t even see because your agent deals with them”.

After graduating with a BA in theatre from Texas University, followed by an MFA in acting from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, she spent her 20s learning to handle those rejections, eking out a living by waitressing between theatre and television jobs. It wasn’t until she had turned 30 that she was spotted by the Coen brothers, who cast her as Gabriel Byrne’s lover in the cult 1990 gangster movie Miller’s Crossing. Three years and four films later, she returned to the theatre for the New York premiere of Angels in America, Tony Kushner’s epic 1980s Aids drama.

So while her film career was carrying her off into the Hollywood stratosphere, her theatre work planted her back squarely in the heart of a community dealing with very immediate horrors. “Angels,” she says, “is a mission play which came at just the exact right time. Boys would stop me in West Village where I lived and say, ‘I took my parents to see it last night and then I told them I was dying.’ The pain of dying and the hope of living with this disease, which is what they did, was so powerful. It was also about the hypocrisy of the time and the abandonment of the government.”

Besides her bursts of mischief, Harden uses social media to channel her political outrage at the more recent hypocrisies of American politics, which brings us back to Sweet Bird of Youth. It is set in small-town America where young black men are lynched by self-righteous mobs controlled by a womanising white plutocrat. “The underbelly of the play is race, hypocrisy, violence,” she says. “The reason I’m doing it is that it does feel like ignorance is being empowered today. There’s a belligerent hypocrisy in the government, and sexual hypocrisy as well.”

But there is another, more intangible dimension to the play, which shadows her personal experience. Del Lago complains constantly of memory lapses, raising the question: are these simply the result of alcoholic blackouts or do they hint at dementia?

Harden became a campaigner for Alzheimer’s research after her own mother was diagnosed with the disease eight year ago. Her eyes fill with tears as she talks about the decision to go public about a condition that she knows is still deeply stigmatised. “I’m aware that other people are bravely speaking up about it, but with my mum I’m braving it for her: when you talk about people with Alzheimer’s you are exposing them, and you have to be aware of it. I did talk to her about it when she was cognisant, but now she wouldn’t be aware of it. It’s a choice made in the interest of change, because Alzheimer’s is a family disease.”

She is wary of overtly imposing such an interpretation on a period play. “Anyway, who hasn’t blacked out and woken up the next morning not knowing what they’ve done? I certainly have.” But she points out that part of the joy of theatre is that it exists in the moment at which it is performed, so even if dementia wasn’t in Williams’s mind, the possibility is available to audiences today.

To underscore this point she makes a surprising detour into her admiration for JK Rowling. She delights in retweeting Rowling’s rants against Donald Trump, but explains a more personal debt too. “When I was going through my divorce, my elder daughter was completely immersed in Harry Potter. I was doing these Hogwarts Thanksgivings and making Bertie Botts’ Halloween candies,” she says.

Her daughter Eulala – who made her film debut aged 18 months in Pollock but has since opted for a life behind the camera – was reading the whole Harry Potter series for the third time. “I wanted to find out what it was all about, so I entered it with her. My son and younger daughter wanted to be in that world with us, so I read it out loud and it brought the four of us together. JK Rowling’s gift to me and to my kids was this world where we bonded deeply into a tight little unit when the rest of our world seemed so messy.”

Once again she returns to Alexandra Del Lago, who turns out not be as washed up as she thinks she is. “She’s an artist – and a writer, an actor, an artist never knows what gift they are giving to other people.”

- Sweet Bird of Youth runs at Chichester festival theatre from 2-24 June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion