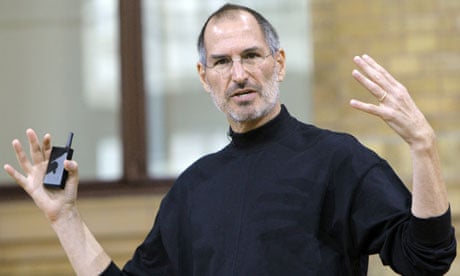

Steve Jobs taught us so many things... To us whose professional life strides tech, ads and media, his way of fostering innovation, of creating an obsessive culture of perfection remains both inspirational and enigmatic. For those who like design and engineering, there isn't a single field Apple hasn't entered – or at least influenced. When I fumble with the appalling multifunction display of my Prius, when I struggle with the remote control of my office A/C, or when I wonder why in hell the $2,000 battery-assisted bicycle I consider buying doesn't have an programmable memory chip to upgrade software that looks forever stuck in version 1.0, I wonder how the Cupertino guys would have handled it. Needless to say, I do the same when I look at media applications or newspapers/magazine designs, many of which seem to have succumbed to a sad mélange of sloppy execution and a lack of decisiveness in design.

For years, I have been reading everything I could about Apple from the management/innovation perspective. As a business journalist, I find Apple being the most frustrating company to follow. Very little comes out. The culture (and the cult) of secrecy extents way beyond any employee tenure; even the usually profligate academic literature is rather bare when it comes to Apple.

However, over a span of 14 years, as it impacted so many sectors, Apple's unprecedented turnaround yielded a few clues. I tried to isolate some with potential applications outside the tech world. What interests me in Apple ranges from its choice of frosted-glass for my MacBook Pro's trackpad (instead of cheaper plastic), to the use of its immense cash hoard, to the way the company prepared itself for the post-Jobs era.

1. Focus. Apple is a $100bn revenue corporation with an extremely small number of products: about 30 different models for four lines of items (computers, phones, music players, tablets). In Jobs's own words: "Focusing is about saying no" (1997 video here). Apple could always be tempted to wade in new markets. Especially since it expanded to the mobile space. Instead, management chose to concentrate on things it could do better than the competition, regardless of alleged customers' expectations or pundits' incantations. For now (as an example), the iPhone comes in one single screen-size (instead of dozens for each of its competitors) and Apple has been adding features only by following its quality-centred agenda.

This is connected to the perplexing question of choices. The news business, whether print or digital, is prone to external and internal influences. On the web, there are alleged "must have" or fashionable features that a digital editor can't avoid. Each editorial fiefdom demands a presence on the home page. It leads to confusion and to the reader's inability to understand what's important, what are the media's strength and sometimes what the site or the app is about.

2. Creativity/design. Not being an engineer actually helped Steve Jobs work better with them, and to connect aesthetics with function:

Some people think design means how it looks. But of course, if you dig deeper, it's really how it works. (...) Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn't really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That's because they were able to connect experiences they've had and synthesise new things.

3. Obsessive attention to details. Last August, Vic Gundotra, a Google executive, shared an anecdote about receiving a Sunday morning phone call from Jobs apologising for an tiny imperfect rendering in the Google logo as displayed on the iPhone. Jobs paid attention to every detail of the business, and demanded a correction right away if necessary. He once said:

Be a yardstick of quality. Some people aren't used to an environment where excellence is expected.

Strangely enough, when you look at the Apple ecosystem there are no discernible ''false notes", disconnects with its environment. The vision expressed at the top cascades down to the lowest level without losing intensity and precision. In his Fortune magazine piece "How Apple works", Adam Lashinksy sums it up:

Jobs himself is the glue that holds this unique approach together. Yet his methods have produced an organisation that mirrors his thoughts when – and this is important – Jobs isn't specifically involved. Says one former insider: "You can ask anyone in the company what Steve wants and you'll get an answer, even if 90% of them have never met Steve."

4. Accountability. It meshes with the previous point and is a key element in Apple's execution process. Accountability is at the cornerstone of Apple's management. Not a single meeting without a DRI – direct responsible individual – in charge of a well-defined piece of the puzzle. At the individual level, it's obviously a double edged sword: the person feels really in charge... of both success or failure.

Here is what Jobs said about its internal organisation at the AllThingsD conference (video here, worth watching):

Do you know how many committees we have at Apple? Zero. We have no committees. We are organised like a startup. We are the biggest startup on the planet. We all meet for three hours once a week and we talk about everything we're doing, the all business. And there is tremendous teamwork at the top of the company which filters down the teamwork through out of the company.

That's Jobs' view of management:

You have to be run by ideas, not by hierarchy.

5. Marketing. Jobs said this about the Macintosh in its 1985 interview with Playboy:

"We built [the Mac] for ourselves. We were the group of people who were going to judge whether it was great or not. We weren't going to go out and do market research. We just wanted to build the best thing we could build."

Twelve years later, he nailed it in Business Week:

"A lot of times, people don't know what they want until you show it to them."

Having said that, once launched every product is supported by a strong market research and analysis of customer choices.

Most of the time, print or digital publishers perform countless pre-marketing studies and focus groups. I have mixed feelings about those. In many instances, it is good to confirm an intuition or to avoid serious mistakes. But it many others, I've seen market studies becoming the tool of choice for managers to evade responsibilities in the event of a failure.

6. Money. Apple is a fabulously rich company ($76bn in cash reserve, more than the US Treasury). Still, resources are allocated in a rather scarce way. But once a decision is made, the company will spend whatever it takes to get the best possible of everything. (The Fortune piece mentions the hiring of the London Symphony Orchestra to record the soundtrack of Apple's video editing software iMovie). Less anecdotal, Apple management won't hesitate to send a product back to the drawing board regardless of the costs. Cash is also used as a strategic weapon: earlier this year, the company disclosed a $3.9bn investment to secure component supplies and production capacity, thus affecting competition. Jobs said at the time:

We've demonstrated a strong track record of being very disciplined with the use of our cash. We don't let it burn a hole in our pocket, we don't allow it to motivate us to do stupid acquisitions. And so I think that we'd like to continue to keep our powder dry, because we do feel that there are one or more strategic opportunities in the future.

Funnily, just one week after this financial disclosure by Apple, AOL announces the $315m acquisition of the Huffington Post. AOL might have some powder left, but no gunner. And I won't mention New sCorp's misfortunes with MySpace.

7. Legacy. Very few companies in the world have set up such a systematic process of mapping out their DNA to make sure it doesn't degrade over time. To do so, Jobs went to the very best in the talent pool: Joel Podolny, at the time dean of the Yale School of Management. Podolny left his prestigious post to work at Apple, in a programme wrapped in secrecy dubbed the Apple University (for more, read this story in the Los Angeles Times titled "Steve Jobs to live on, virtually, in Apple University").

I'm particularly sensitive to Apple's lessons. For one, I had the luck to work for a Norwegian company which invested a lot to learn from others' experience. Schibsted ASA's management willingness to understand others' success and failures played a significant role in its achievements.

Secondly, as someone who loves journalism and the media business, I'm preoccupied by what I see as an unprecedented wave of mediocrity sweeping through the news business, which suffers from deteriorating business models coupled to questionable management.

At the same time, I really believe most media companies can deal with such challenges by finding out what their DNA is really about, by doing whatever it takes to preserve it, and build its future on such a foundation.

One final note. Take 40 seconds to watch this video showing Steve Jobs responding to a student who recently asked him what he would add to its famous 2005 Stanford speech.