Student days

The roots of Julia Gillard’s political career stretch back to 1982 when she moved from Adelaide to Melbourne to take a job as the education vice president of the Australian Union of Students (AUS).

Student politics has long been a training ground for those with political ambition. For Gillard it was an introduction to her generation of Labor politicians and unionists, including to Michael O’Connor who was for a time her partner, is now national secretary of the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union, and has has been a lifelong friend.

The AUS was a left-dominated organisation but Gillard was less radical than many members

She overcame factional opponents and won pre-selection for Labor in 1998

She was AUS president in 1983 and later also worked part-time for the Socialist Forum, an organisation formed by former members of the communist party and Labor Party members like Gillard, until she finished her law degree at the end of 1986. The time with the forum taught her a lot about the divisions within the ALP left, particularly in Victoria, which would for a time thwart her political ambitions.

Legal minefield

Controversy surrounding Gillard’s period at the law firm Slater & Gordon has followed her throughout her political career. After graduating from the University of Melbourne in 1986, she went to work for the law firm, becoming a partner in 1990 at the age of 29.

Gillard worked in the industrial department, representing trade unions in cases against employers. She was at that time in a relationship with Australian Workers’ Union official Bruce Wilson. While in that relationship, she provided advice about the establishment of a reform association. No file was opened on the work, and she did not brief other partners at the firm at the time. The AWU reform association (which has since been described as a “slush fund”) is now the subject of an ongoing police investigation. Wilson has denied any wrongdoing in the matter.

Gillard ended her relationship with Wilson in 1995, and her role in establishing the association fractured relationships between her and some of her colleagues at Slater & Gordon. (There was “growing tension and friction amongst the partnership”, Gillard said in 2012 of that time.) She was subjected to an internal review. "Ms Gillard co-operated fully with the internal review and denied any wrongdoing," Slater & Gordon said in a statement released in August 2012. "The review found nothing which contradicted the information provided by Gillard at the time." Gillard left the firm shortly after the review.

Gillard’s role in establishing the association fractured relationships with Slater & Gordon colleagues.

The controversy was first raised in the Victorian parliament in 1995. It surfaced again in newspaper coverage in late 2011. Labor backbencher Robert McClelland raised allegations related to the AWU in parliament in June 2012, triggering another round of media investigations. Gillard held a lengthy press conference in August 2012 categorically denying any wrongdoing and saying she had no knowledge of the associations operations. She argued that she had been the subject of a sexist smear campaign.

Taking a seat

It took Gillard five years and three attempts to win a seat in parliament. She sought pre-selection for the seat of Melbourne in 1993 but was beaten by fierce rival and soon-to-be ministerial colleague Lindsay Tanner. Senator Kim Carr, a factional leader in the socialist left, and also later a ministerial colleague, also strongly opposed her candidacy.

She then tried for a place on the Victorian Senate ticket for the 1996 election, again opposed by Tanner and Carr. She was eventually and belatedly offered the highly uncertain third position and lost.

She overcame factional opponents and won pre-selection for Labor in 1998

After working for Victorian opposition leader John Brumby as chief of staff she finally overcame her factional opponents and won pre-selection for the safe outer-Melbourne seat of Labor in 1998. She entered parliament aged 37.

Policy from opposition

Gillard entered the shadow cabinet in 2001, just after Labor lost the Tampa election. National security and boat arrivals had dominated the political discussion, to Labor’s electoral cost. Under the new leader, Simon Crean, Gillard was given responsibility for immigration and for redrafting Labor’s policy.

The party was divided over policy direction. Key left figures, including Carmen Lawrence, were openly critical of mandatory detention and harsh deterrence measures. Gillard was given the task of striking a middle course, and produced a new policy in 2002 which maintained mandatory detention and processing at Christmas Island – although it committed to winding back some elements of the Howard regime.

Gillard was given the task of striking a middle course on immigration

Gillard left the portfolio before a new policy was endorsed at Labor’s national conference in 2004. She remained loyal to Simon Crean until he lost the party leadership, then swung her support behind Mark Latham. By then Gillard was Labor’s health spokeswoman (shadowing Tony Abbott as health minister), and Latham gave her the role of manager of opposition business.

Gillard developed the Medicare Gold policy, which tanked after the Coalition claimed a $5 billion hole in the costings. Labor lost the election and Latham quit politics in 2005. Kim Beazley returned to the leadership. Gillard announced she would not contest the position in 2005. She later combined with Kevin Rudd to see off Beazley in December 2006. Gillard became Rudd’s deputy, and was installed as deputy prime minister after Labor’s victory at the 2007 poll.

Government by Gang of Four

Gillard was sworn in as deputy prime minister in December 2007 – the first woman to have held the position. Rudd gave her responsibility for the mega portfolio of employment, education and workplace relations.

Gillard was charged with dismantling John Howard’s unpopular WorkChoices regime and replacing it with the Fair Work Act. She had to strike a balance between demands by unions to introduce more regulation and demands by employers that the pendulum not swing back too far.

She also embarked on significant reforms to education, her personal passion. Gillard was regarded in this period as Labor’s strongest and sharpest parliamentary performer, and a good foil to the more process oriented style of Rudd.

Gillard was regarded as a good foil to the more process oriented Rudd

But the government was lurching towards an internal crisis. The hectic pace of policy change, and Rudd’s leadership style, led to internal and external criticism of micro-management by the prime minister. MPs and some cabinet ministers felt frozen out by Rudd and the so-called “gang of four” – Rudd; Gillard; the treasurer, Wayne Swan; and finance minister Lindsay Tanner, who were the members of the strategic priorities and budget committee of cabinet. They were the principal decision-makers during this period, with cabinet and caucus often rubber-stamping their deliberations.

The shine came off Rudd with voters, and Labor slumped in the polls. The government was under assault by the major mining companies over a plan to impose a super profits tax on the industry, and Rudd could not secure parliamentary support for his carbon pollution reduction scheme. The Labor leadership came to a head abruptly in June 2010.

Leadership for the taking

Photograph: Mark Graham/ AP

The government’s internal crisis came to a head on 23 June, 2010. The day was extraordinarily chaotic. Labor backbenchers and some ministers were assuring journalists that nothing was happening with regard to the party leadership, while Gillard and Rudd were in fact locked in crisis talks in Rudd’s parliamentary office.

Gillard had made several public assurances that she would not seek the party leadership, and senior figures were divided over whether it was in Labor’s interests to bring down a prime minister yet to complete his first term in office. But key right and left powerbrokers in New South Wales and Victoria had lost confidence in Rudd’s capacity to win the 2010 election – and moved against him after a period of destabilisation.

Gillard declared that a good government had lost its way

Gillard and Rudd met in the morning and again in the late afternoon. Accounts of the meetings vary but Gillard is said to have first given Rudd an undertaking that he would have more time to stabilise his leadership, then reneged on that undertaking when it was clear that she had the numbers to win a ballot.

Rudd initially indicated he would fight to hold his position, but then gave way to Gillard, who was elected leader by the Labor caucus on 24 June. Wayne Swan assumed the deputy leadership. Rudd, flanked by his family, had a tearful farewell press conference in the prime minister’s courtyard, and went to the backbench. Gillard, with an election in sight, attempted to put Labor on a new footing by declaring that a good government had lost its way.

The real Julia

Only a few weeks after the leadership change, Gillard called the election for August 21. Labor wanted to capitalise on its bounce in the opinion polls. Her initial campaign slogan was “moving forward” – an effort to move Labor past Rudd and the aftermath of the coup, and to project a positive second-term agenda.

But Gillard found herself unable to move forward very far at all. Labor’s campaign was plagued by leaks and by the appearance of internal disunity. Gillard was also attempting to assume a new prime ministerial identity – to move past her role as deputy and parliamentary attack dog – in only a few short weeks. The result was confusing to voters, and Labor’s poll recovery evaporated.

Gillard declared in early August that the “real Julia” would return to the fray, and would assume control of the campaign. “I’m going to discard all of that campaign advice and professional or common wisdom and just go for it,” she declared on August 2.

The resulting hung parliament was Australia’s first since the second world war

Tony Abbott’s highly successful anti-carbon tax campaign left many Australians believing, incorrectly, that Gillard had promised not to have a carbon price at all. The carbon tax “lie” seriously eroded Gillard’s political credibility.

Further chaos ensued when Gillard was confronted on the campaign trail by Latham, a guest reporter for a TV network. Opposition leader Tony Abbott, by contrast, managed to run a tight campaign, with few stumbles beyond a messy first week. The result of the circus was a hung parliament, the first one federally since the second world war.

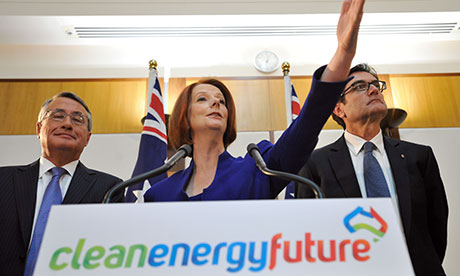

The carbon mistake

After the Rudd government’s emissions trading scheme was defeated in the parliament, Julia Gillard and Wayne Swan argued Labor should ditch the policy, but other ministers strongly disagreed. Rudd eventually decided to defer it. His support plummeted, weakening his position in the leadership showdown with Gillard that was just weeks away.

After she took the prime ministership, Gillard promised an emissions trading scheme, but only after she had established a community consensus, including through the much-derided “citizens assembly”. But in the days before the 2010 election, she promised there would be “no carbon tax under a government I lead”.

After the election, when she established a committee with the independents and the Greens to negotiate an emissions trading scheme, the only way to overcome the previously intractable differences between Labor and the Greens over the ultimate ambition of the scheme was to start with a three-year fixed price – effectively a carbon tax – before moving to the promised trading scheme with a floating price.

Gillard was regarded as a good foil to the more process oriented Rudd

Gillard has conceded she underestimated the political impact of an effective tax for three years, when she had promised there would not be one.

Tony Abbott’s highly successful anti-carbon tax campaign left many Australians believing, incorrectly, that Gillard had promised not to have a carbon price at all. The carbon tax “lie” seriously eroded Gillard’s political credibility.

The misogyny speech

On 10 October 2012 Gillard delivered her now famous misogyny speech which went viral around the world. “I will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny by this man, I will not,” she said pointing to Abbott across the despatch box. “And the government will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny by this man. Not now, not ever. The Leader of the Opposition says that people who hold sexist views and who are misogynists are not appropriate for high office. Well, I hope the Leader of the Opposition has got a piece of paper and he is writing out his resignation.” The speech was viewed more than 2 million times on Youtube and lauded by feminists around the world.

‘I will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny by this man, I will not’

The immediate context of the speech was a debate over the future of the then speaker Peter Slipper who had made disparaging references to female genitalia. But the broader context was what Gillard said was a pattern of misogynism, including the anti-carbon tax rallies attended by Tony Abbott were protesters carried placards saying “Ditch the witch” and “Bob Brown’s bitch”. Gillard was regularly referred to as Ju-liar by radio announcer Alan Jones, who also suggested Gillard should be “should be tied in a chaff bag, taken to sea and dumped.” In a speech to the recent press gallery ball, Gillard commented on the “sheer irrationality of it”...I feel like ringing up and saying ‘oh for god’s sake Alan, don’t you know you can’t drown a witch.”

Unfinished business

Speculation that Kevin Rudd could challenge Julia Gillard escalated in late 2011. Rudd, who was foreign minister, denied he had any intention of mounting a challenge and said he supported the prime minister. In February 2012, after a backbencher called on Gillard to stand aside, a video entitled “Kevin Rudd is Happy Little Vegemite” was anonymously uploaded on Youtube – showing out-takes of an attempt by Rudd to film a message in Mandarin for the Chinese community when he was prime minister. In the out-takes he is repeatedly swearing and banging the table in frustration. Ministers accused Rudd of disloyalty.

Rudd, in Washington, resigned as foreign minister and came home to consider his next move. Ministers lined up to denounce his record as prime minister, in a determined strategy to “kill off” his ambitions for ever. Gillard called a leadership ballot for 27 February, which she won 71 votes to 31.

Minutes before the ballot was to be held, Rudd announced he would not stand

But leadership speculation again intensified in March 2013 and Gillard again called a ballot. Just minutes before the ballot was to be held, Rudd announced he would not stand, saying he had made it clear that the only circumstance in which he would return to the leadership was if there was an “overwhelming majority of the caucus” supporting him.

Gillard was re-elected unopposed. But as Labor’s polling worsened the leadership speculation still continued.

The denouement

In mid 2013, predictions that Kevin Rudd would make a play for the leadership increased in the last week of sitting parliament before the federal election. The window of opportunity for any challenge shrunk further with the news that Rudd would fly to China on the Thursday.

On the morning of Wednesday 27 June, two key Gillard supporters – independents Rob Oakeshott and Tony Windsor – announced their retirement from politics. Then, independents Bob Katter and Tasmanian Andrew Wilkie announced they would support Kevin Rudd in a confidence motion.

The writing was on the wall, as news circulated that a petition to call a special caucus meeting to discuss the leadership was doing the rounds of Labor party members. Gillard called a ballot, and a short time later Rudd announced he would stand. Factional powerbroker Bill Shorten announced he had switched his support to Rudd.

‘Gillard accepted defeat with composure, congratulating Rudd and calling on the party to fight to win the election’

Gillard – now a former prime minister ousted in a similar style to the manner in which she took the leadership – accepted defeat with composure, congratulating Rudd and calling on the party to fight to win the election. She reflected on the division in her party and the difficulties in leading a minority parliament. She also spoke of her role as Australia's first female prime minister.

"What I am absolutely confident of is it will be easier for the next woman, and the woman after that, and the woman after that, and I'm proud of that," she said. Referring to recent sexism against her and accusations of "playing the gender card", Gillard said, "The reaction to being the first female does not explain everything about my prime ministership and does not explain nothing about my prime ministership.”

After the press conference, Gillard tendered her resignation to the governor general.