Shooting star - Leyland P76

Shooting star - Leyland P76

Shooting star - Leyland P76

|

|

Shooting star - Leyland P76

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

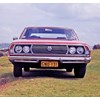

It’s 50 years since Leyland’s spectacular P76 burst on to the Aussie scene. While it may not have survived the tough local market, it had a lot going for it. Glenn Torrens talks with the people who were involved at the time.

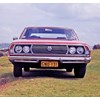

It was a big, bold plan. Create a big, bold new Aussie car to take on Aussie’s ‘Big Three’ of Kingswood, Falcon and Valiant.

It was an even bigger, bolder plan when you consider who did it: BMC Australia. Foreign ownership of our ‘Aussie’ cars wasn’t a big deal: GMH, Ford and Chrysler all had roots in, and tech from, the USA and by the late 1960s, Japanese cars (in particular Toyota and Datsun (Nissan) were being assembled here in ever increasing numbers.

But BMCA’s specialty was front-drive smaller cars based heavily on UK designs: Cars such as Mini, Moke, Morris 1500 and Austin 1800, plus its later Kimberley and Tasman derivatives… Not rear-drive bigger cars.

So what was the team at BMC Australia (later renamed Leyland Australia) thinking when it conceived the big, bold, rear-drive P76?

It had high hopes it could drag ‘average’ Aussie car design out of its 1960s doldrums; it was aiming for European standards of technology and equipment; of ride and handling, infused to the cavernous size body that Aussie fleets and families favoured. With that, there was hope the Aussie company could rise above its pommy parent’s lack of new product during the 1960s.

You could say things didn’t begin well. Among other company issues, the P76 development budget was less than $25M. To put that in perspective, just a few years prior, Ford Australia announced an $31M expansion plan. In other words, a renovation of its existing facilities - not a new car.

Despite its cut-price development, the P76 glowed with fresh ideas. It was the first Aussie-designed car with strut front suspension; light, compact, durable and good for handling. Struts helped the P76 be around 150kg lighter than the ‘average’ Big Three despite it being bigger inside and out.

Another techy tid-bit was the rack and pinion steering. Some others (Torana; Cortina – both based on European designs) had R&P but it was an innovation for the ‘full size’ Aussie car. Front disc brakes were standard when the Big Three’s base cars had drums. P76 even had four-way hazard warning lights.

The windscreen wipers were semi-concealed behind the back edge of the bonnet; another feature not seen with Aussie style/design for another 15 years (on EA Falcon/VN Commodore). Also hidden was the construction technique of using large body sections; the P76’s shell was reportedly constructed using fewer pressings than a Mini and should have resulted in a better built body.

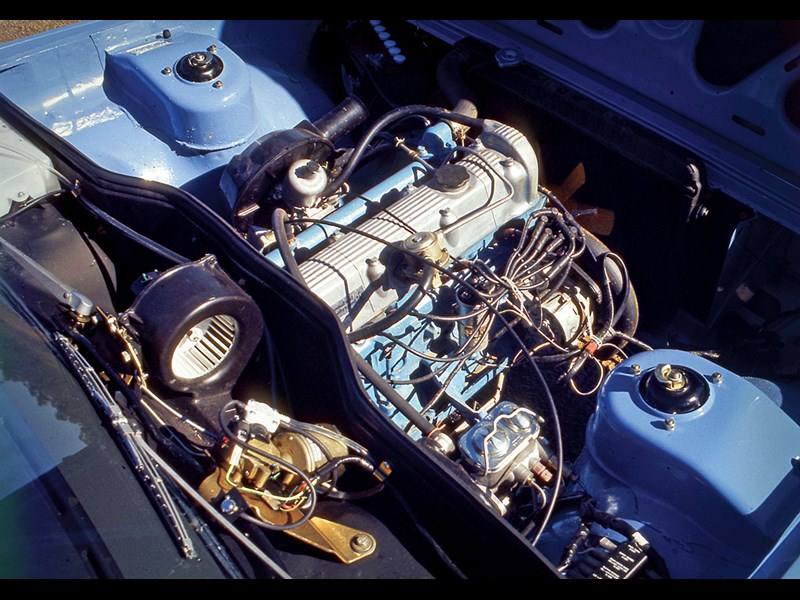

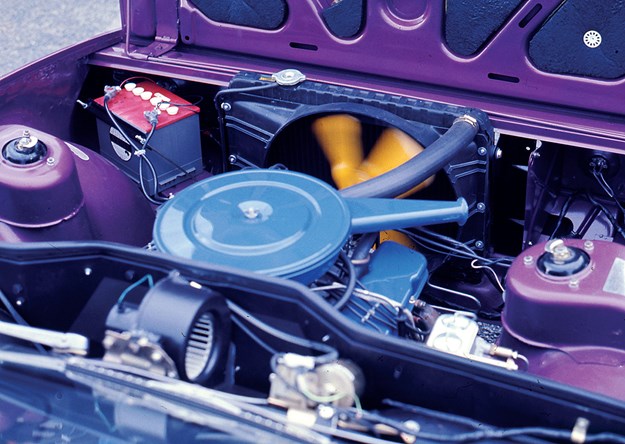

The Leyland P76’s base engine was a 2.6-litre (160ci) carb-fed straight six with an overhead cam (shared with the Torana-sized Leyland Marina). Its top-spec 4.4-litre V8 was a light and powerful all-alloy unit so both engines introduced ‘anything but average’ features.

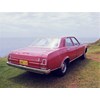

The Leyland P76 V8 Executive was judged Wheels magazine’s Car of the Year for 1973.

However, the P76 was not without its flaws. Due to a combination of the budget-priced and rushed development and a stressed factory, it suffered from assembly/quality woes. By some accounts it was no worse than average but for a whole bunch of reasons the Leyland has unfortunately come to be regarded as a ‘Lemon’. Sadly, part of the P76’s legend these days is the fact it’s been the butt of jokes for decades.

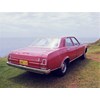

Leyland Australia collapsed; the Aussie P76 died in November 1974.

The exploding star life of the Leyland P76 is a fascinating and proud, yet frustrating and tragic part of Aussie motoring history.

THE RALLY BLOKES

WHEN IT WAS new, rally competitor John Bryson teamed with successful trials/rally driver – and also motoring journalist and ex-BMCA PR man – Evan Green to prepare a P76 for the 1974 World Cup Rally, a gruelling long distance event (19,000km!) that looped from London England to Munich Germany via the Sahara Desert and Nigeria in southern Africa.

With Leyland Australia support, Bryson and Green project-managed (and themselves did plenty of work on) the car. The main sponsor was men’s cologne brand Faberge Brut 33 (how ’70s is that?!) giving it the ‘Big Brut’ nickname.

As anyone who has read Green’s account of the event A Bootful Of Right Arms will realise, the ’74 Cup was tough. In an international field of 70 cars, just 19 finished. The Bryson/Green P76 was one of the 19 with a creditable 13th overall after suspension problems in the Sahara Desert cost a higher place. The Bryson/Green duo won the Sicilian Targa Florio competitive stage outright; the inspiration for the P76 Targa Florio model.

The P76 participated in the 1970s Castrol Southern Cross Rally and Repco Around Australia Rally, too.

Matt Byson has continued his late dad’s rally prowess, entering the P76 in classic – but tough – rallies of today.

"I entered a rally in 2012 in America called the Trans America Challenge," Matt begins. "It started in New York and finished in Alaska; it headed south, across the Andes; up through Canada to Alaska to a town called North Pole."

Matt began with a New Zealand-assembled car, already with a protection cage. "That saved time," explains Matt. "Every other aspect of the car was built for high performance for long distances over tough terrain. But it ended up being not as super-challenging or as tough as we thought! It was a lot more about navigation and regularity rather than grunt and speed.

"We finished second. We got to the end and Gerry (co-driver, the late Gerry Crown) said ‘This car is too good to not do the Peking to Paris rally!’

"So we did that in 2013. We won, beating a Porsche 911. In 2015 we did an event called the Road to Mandalay." This event went through Malaysia, Thailand and Burma. "We finished second, by one second, to that same Porsche we’d beaten in the Peking-Paris," recalls Matt. "It beat us by one second, on the last stage, after 28 days of competition… That’s motorsport!

"In 2016 we did the Peking to Paris again; but we had a few dramas so finished sixth. We crashed…"

"In 2017 it was the Samurai Challenge around Japan. It was a bunch of different activities – speed events and navigation; tarmac rally, race tracks etc. We were sixth outright, first in class and first in speed. Some of the roads in Japan are very narrow – they seemed narrower than the car!

"In 2018 it was the Road to Saigon. We came second – we would have come first but for a bad batch of fuel…

"In 2019 it was Peking to Paris again, which we won over another Porsche."

That’s an impressive set of results for a big Aussie car that was – and continues to be – the butt of jokes.

"Dad did a lot of rallying; a lot of it long distance – such as the World Cup – as he was a factory driver and navigator for all sorts of factory cars," says Matt.

"He always said the Leyland P76 was the best long distance rally car he ever drove."

THE RESTORER

BRAND JUNKIES come in all shapes and sizes but there are few more dedicated to a badge than Australia’s hard-core Leyland P76 freaks. Stuart Brown is one of those and has enjoyed decades of driving, modifying and – more recently, through his Ausclassics biz – restoring P76s.

For Stuart, it began with his parents buying a brand new Leyland P76 for the family of six in 1973.

"Dad had quite a thorough look at all the alternatives," remembers Stuart, who was a kid at the time. "Ford, Holden, Chrysler – he drove them all. I have all the dealer brochures he collected from that time!

"Eventually, he chose the P76. It had more room for a family and it went better."

The Browns’ new family car was a bench-seat Deluxe auto V8. It was bright yellow because the Browns lived in Bathurst (actually on Conrod Straight, Mount Panorama – what a cool address!) and the colour was regarded as safer for travelling over the often foggy Blue Mountains.

"We drove it everywhere and it didn’t give us any trouble. Nothing," reckons Stuart. "In November ’84 when it became my first car, it had covered more than 100,000km.

"I added a few bits; I enhanced it. That included bucket seats and air conditioning, plus Targa Florio wheels, the dual headlights and I painted the sills and window frames. It had everything!"

As an officer cadet Stuart took the car with him to Duntroon in Canberra.

"I used to drive it a lot. For fun, I used to go for drives on a Friday night instead of going to the pub."

Unfortunately the ‘yellow rocket’ was written off by a fellow student, who’d borrowed it, in 1987. Stuart decided to re-shell it.

"I’d grown up building plastic model kits, so I thought this was the same but simply on a 1:1 scale!" The result for that car was a win at the 1988 Victorian P76 Concours.

That was Stuart’s introduction to vehicle restoration. Soon he and his brother Craig found fun - and funds – in resurrecting tatty P76s.

"We’d buy one for $500, then give it a complete clean and service and fix all the rattles. Then we’d sell it and go buy another one and do the same. We paid for uni, made some money and owned and drove some nice cars."

As do others, Stuart mentions that the sudden factory shut-down in 1974 was – ironically – a factor in keeping so many P76s alive. There wasn’t the usual ‘run-out’ process of a superseded car so there were piles of spares.

"It was a factory full of everything," says Stuart.

But by the mid-1980s, the big glut of ex-factory P76 new spare parts was beginning to thin-out. Stuart specifically mentions the humble front indicator lenses as being immensely important.

"Someone had their brain switched on when Lucas [maker of Leyland electrical parts such as lights] shut down," explains Stuart. "They found the original moulds for the front indicators. The Victorian club (of which Stuart’s dad was president) got hold of the tooling.

"I reckon if it wasn’t for the recreated indicator lenses, lots of P76s would have been scrapped," explains Stuart.

"Plus, it motived people. It made them think: ‘Well, we’ve got these, what else do we need? What else can we do?’

"As a group, P76 people have done lots of stuff. The fact we – me and others – have made lots of bits means lots of people can keep their cars going."

Stuart’s most recent project with his brother was a Nutmeg P76 Super loaded with power steering and air-con and upgraded with five-speed box and four-wheel discs. It won Best Restored at the recent Leyland P76 Nationals that celebrated 50 years of the P76. Fittingly, it was a car for their dad, Michael!

THE SALESMAN

HAL MOLONEY was a salesman for Trigg’s Motors, the Leyland dealer in Toronto, NSW, a lakeside location 2hrs north of Sydney and halfway between the larger coastal centres of Gosford and Newcastle.

"It was a good sized town," Hal explains. "Back in the day there were several coal mines operating in the region and there was a lot of people around."

As was the case for many suburbs and towns across Australia, the Leyland dealer wasn’t too far from the local Holden and Ford dealers so there was plenty of shopping around. Surprisingly, Hal reckons the Leyland’s advanced design features – such as the rack and pinion steering and alloy V8 - weren’t always a priority for customers.

"For most people it was matter of: ‘Do we want the six or do we want the V8?’ Most of the innovation of the features under the skin went un-noticed. I can’t recall too many people considering all that stuff as a priority."

According to Hal, how the Leyland drove, thanks to that good suspension and light weight, that was the difference to the Big Three.

"Once you got them into the car for a test drive, they usually bought one."

Not everyone had the same priorities.

"One day, an Army bloke came in and said he was interested in a six-cylinder one. I pointed him to a brown one on the showroom floor. He went over, sat his bum in the seat, slung his legs in and said: ‘Thank you - I’ll take it!’ He hadn’t even taken it for a test drive. Then he explained: ‘Did you see what I did there? I have issues with my legs and I can’t sit in a Ford or a Holden and swing my legs into the car like that.’ That’s all he wanted. He was thrilled!"

Quality? "We had very few issues with them," says Hal. "Our service manager, Chris Grey; he and I used to chat. Generally nothing much went wrong. I remember a couple of intake manifold gaskets and that’s about all."

So there’s truth in the rumour of a few early build cars doing lots of damage to the reputation?

"That’s correct," says Hal. "Overall, from the ones I saw, they were pretty good. We couldn’t get enough stock. We were constantly asking for more trucks to be sent up: ‘We don’t care what colours they are! Just send ’em up!’"

Hal was sitting in a factory supported P76 rally car, at the Sydney Opera House, waiting to be flagged off on the 1974 Southern Cross Rally, when he heard of the company collapse and the axing of the Leyland P76.

"Evan Green [fellow P76 competitor] was just up in front of me and a company exec, Guy Kendall came down and told us; ‘It’s finished – but we’ll honour our commitment to your rallying. You’ll get your money…’ It was a difficult message and he treated us well.

"It was quite a shame. We had our hearts set on selling these cars; it was a terrific Aussie car."

As did others, Hal had good success with the P76 as a rally car. Not only did he compete in the 1974 Castrol Southern Cross, but in the Repco Round Australia in 1979 and the Mobil-1 Around Australia Trial in 1995, where he managed to finish ahead of Holden racing legend Peter Brock’s factory backed Commodore!

THE APPRENTICE

"I was an apprentice fitter and turner, " begins now-retired Australian automotive industry stalwart Mike Breen. Known and respected for his long service with Toyota Australia, he was there during the exciting times with a hopeful Leyland Australia.

"In those days the factory had a three-week annual leave over Christmas, so over 1972/73 we had those three weeks to work on the production line in the press shop," he explains. "We had to reposition all the jigs and spot-welders; pull down all the pipes and equipment and put them back together again."

"We worked 12 hours a day seven days a week."

Mike offers some insight into the P76’s quality problems and the incredible, if somewhat futile, efforts to make the P76 the best built of the Aussie cars.

"There were a lot of prototypes [going] down the line trying to get everything ready; the jigs, especially. They were a bit of a problem…

"Leyland introduced this scheme called the Buyer Protection Plan. At the time, Leyland was copping a hammering for its quality control. It had to do something; it had to prove to the people it was addressing all the issues.

"What happened there was; Marinas and P76s all went up to what was known as CAB3 [Car Assembly Block] which used to be where they built the MGBs and Midgets. Anyway, that area was converted to a quality control area. They put a big group of people in there including mechanics and engineers. The cars went there to get fixed. But, really, it was a patch up.

"The P76s; sometimes you’d get something like an auto car with a clutch pedal. Unfortunately things like that happened a lot. At first, the jigging wasn’t right; panel gaps - sometimes you could fit your thumb through a door gap. I ended up driving a lot of P76s and some of them; if you drove through a car wash or in the rain, you’d end up with the heel area of your trousers wet from the carpet.. If you drove on a gravel road, dust would come in…"

Mike offers insight into the willingness – or desperation - of Leyland to get its P76 into showrooms.

"A lot of the first ones weren’t supposed to be sold to the public," he explains. "They were all company cars. But around the time they started to build the P76 there were strikes [industry disruptions] everywhere. There were [electricity] power shortages; there were supplier shutdowns. For instance, glass: there were cars off the production line without front or rear windscreens.

"But the dealers were screaming for stock to sell."

So as Mike explains, to help satisfy demand, these earlier company cars – not much better than test-builds, with a higher-than-average infection of problems - were sent for sale, amplifying the P76’s poor reputation.

"Those cars were supposed to be crushed."

As others have confirmed, outside as much as inside influences caused problems.

"Everything that could go wrong, did go wrong. It wasn’t really the fault of the car."

THE ENGINE MAN

Noel Deforce began his fitting and machining apprenticeship at BMCA in January 1964.

"About halfway through the third year of my apprenticeship they put me in the Experimental section for three months," he explains. "At the time, moving people around to get experience with different aspects of production was routine for the company."

Noel was interested in engines and motorsport. That must have been noticed by someone higher up the food chain because not only was it odd for an apprentice to be placed in the top-secret Experimental section, but after the three months Noel was asked to stay.

"There began my involvement in the P76."

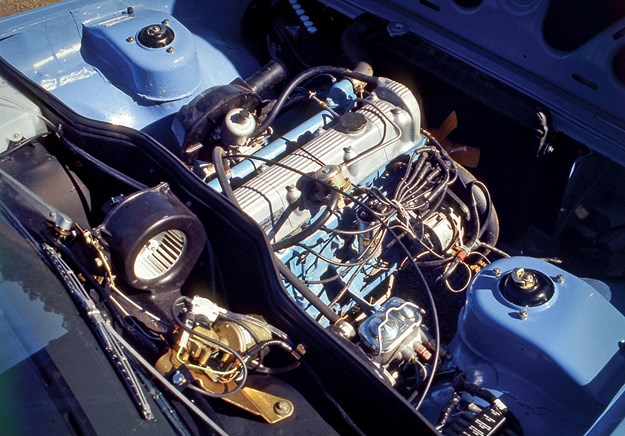

The small team Noel was in had a big job: develop the two engines planned for the P76’s launch: the 2.6-litre OHC six and the all-alloy 4.4-litre V8.

"I had a passion for engines. I was there for the six-cylinder and V8 development right from day one," he continues. "We had a dyno room with three dynos, and an engine assembly area. My role was to help with engines for development plus durability and endurance testing."

Although not a clean-sheet design, the all-alloy V8, especially, was an involving project.

"We started with the Rover engine," Noel says. "Most people know that to be an ex-GM design of 3.5-litres. By the time we finished with it there wasn’t much that wasn’t changed: ours had a taller block to allow a capacity of 4.4-litres; the taller block was much nicer to our longer stroke. We gave ours a new manifold to take the Australian dual-throat Stromberg, like what Holden had."

Noel offers some fascinating insight into the ‘can-do’ attitude - and the teamwork - involved in developing the P76 without the huge facilities of the US or Europe.

"The first castings for the blocks were machined in the Lithgow Small Arms Factory," Noel reveals. "And part of the development of the new intake manifold involved cutting Perspex windows into the runners so we could see the effects of the gas flow. That was clever stuff in the days before prototype computer simulations. Lynx Engineering (a Sydney performance company) also did some work for us. In fact, after Leyland closed, I worked there for a year."

The durability testing of the new all-alloy engine was critical. Noel mentions testing the engine at wide-open throttle (full power) with the dyno cycling the engine from 1000 to 5000rpm for 500 hours; that’s around 20 days of constant running for the equivalent of nearly 50,000km, flat-out!

After the engine’s specifications and durability targets were met, on-road testing began. However, unlike the Big Three, BMCA didn’t have its own secret vehicle test track so some clever thinking was required.

"I wasn’t hands-on with their construction but they made some prototypes by splicing P76 floors into Holdens." Noel says. "That way, we could test the engines and other parts on-road without anyone knowing what we were doing. One of the trips I did in those cars was out to Nyngan (western NSW) to do fuel consumption testing."

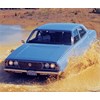

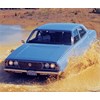

Charleville in Qld was another BMC/Leyland testing destination; its rough roads and dry conditions – and sparse population – made it perfect for hammering the P76’s secret new strut front suspension and rack and pinion steering, coil rear and, later, the car’s dustproofing. Four or five cars would be out there being tested for a couple of weeks at a time.

"The cars’ critical dimensions were measured before and after each trip," explains Noel. "That way, any discrepancy due to wear or distortion could be assessed. They were designed well and they were light. They were only 1230kg which was great for durability; they were light on their feet.

"It drove like a smaller car," says Noel. "It was as good as, or better than, an early Commodore but we did this years earlier.

"We knew the whole car was way ahead of its time."

THE PR MAN

WILL HAGON is a respected Aussie motoring journalist and broadcaster who was Leyland Australia’s PR Chief at the time of the P76’s launch.

Will was, of course, aware of the secret new Aussie car when he was called to a meeting with the Engineering Director Dave Beech. Also in the meeting was Leyland’s English boss, Lord Stokes.

"We were talking about the plans for a ‘Model A’ and ‘Model B’ [the intended small/med and large/P76 sized cars for Australia]" says Will. "Stokes said, ‘Well, we can’t just call it a ‘Model B.’ That means second-best.’ He was playing with his watch, which had his old [military service] number on it and he read it out aloud [as a suggestion]. It was ‘P76’ something-or-other.

"That’s how the P76 was named."

Maybe the apparent flippancy of the car’s naming process only reinforces the legendary disdain the English BMC/Leyland bosses had for the new model… And Australia in general.

"Evan [Green – Will’s former boss] told me of a time he went to England to talk about how the cars worked in Australia. One problem was dust getting into the boot of Austin 1800s. The Poms were not the slightest bit interested in solving the problem. The 1800 worked well in England, so nothing was about to change for the remote and small Australian market."

However the hard-working Aussie staff – including Will, of course – did their best to ensure the P76’s success.

"I was in charge of doing the P76 media kits; organising the photography, getting all the stuff written and running-in the road-test cars," explains Will. "I wanted the press kit folder to be silver to reflect the aluminium V8 engine that was such an important part of the car," he continues. "The car had a terrific badge on the front guard and through the production people, I organised 20 of those for the media kits.

"This was a significant Australian car so I decided it should be launched in Canberra – the capital of Australia. We had a section of the drive route to the space tracking station at Tidbinbilla. We also had a closed off dirt track section. One of the testers was John Keran, a rally driver working for the Sydney Sun. We got pictures of him opposite-locking the car and saying: ‘This car is sensational. The handling is terrific!’

"In particular the V8 was outstanding. It handled better than anything of the time."

So, Mister PR man: Does the P76 deserve its reputation? Well… no. But yes.

"The Australian engineers and the production people were fantastic," answers Will. "They understood the conditions here and designed appropriately, putting in some unique features. Within very difficult limitations, they did a good car."

But that wasn’t enough.

"I remember talking to Roger Foy – one of the local development engineers – and he said: ‘We’ve not had the time to go to the next stage, to get cost out and make components look better,’" relates Will. "Ford or Holden, at the car’s development stage, would be going through all the little parts of the car and making them better."

There were production problems at Leyland’s Zetland (Sydney) plant, too.

"The biggest car previously built on the P76’s main assembly line was the Austin 1800. But the P76 was wider, so, ideally, the production line needed to be wider - but the [parent] company in England didn’t have the money.

"There was a sequence along the line where the doors were put on, the car moved on a way and then the doors were taken off! As well as doubling-up, they had to be put somewhere before finding their way back to the right car."

Could those problems have been overcome? Probably. However, news broke of the English parent company’s financial woes.

"A journo from The Sydney Morning Herald came to talk about Leyland’s finances and P76 sales. We defended it as best we could… but that became front page news.

"The car wasn’t selling enough. The company was short of money. I’d had five wonderful years but could see where things were headed. Before the bomb fell, as it were, I left.

"The car was basically a good car. It had a lot going for it – especially the alloy V8 [model].

"If one of the other brands had done this, it would have been a roaring success."

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)