Hannah Hoch / Anna Therese Johanne Höch

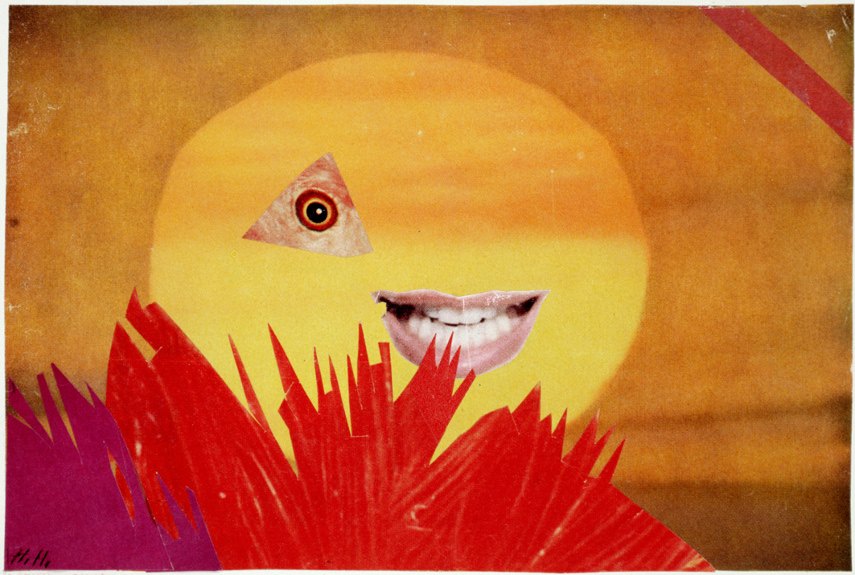

Prized for her pioneering collage and photomontage artworks, Hannah Höch was not only a rare female individual practicing prominently in the arts of the early twentieth century but was also consciously and successfully promoting the idea of women working much more creatively in the modern society[1]. This artist made a practice out of appropriating and rearranging images and text gathered from the mass media, usually with goals of mocking and critiquing the Weimar German Government. Inspired heavily by the avant-garde works of Pablo Picasso and her fellow Dada exponent Kurt Schwitters, Höch's dynamic and layered style managed to fit right in with some of the greatest names in modern art history. It should also be noted that Hoch much more preferred metaphoric imagery[2] to the violent and direct techniques commonly found in her contemporary colleagues, such as the extremely confrontational approach of John Heartfield.

A Tough Youth and World War I

Höch was born Anna Therese Johanne Höch during the year of 1889 in Gotha, the fifth-largest city in Thuringia, Germany. Her tough childhood reached its unfortunate peak when young Anna was forced to start taking care of her youngest sibling Marianne despite the fact she was still going to school herself. However, this dire situation did not dishearten her as Höch managed to make ends meet both for herself and her family. In 1912, Höch began classes at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin where she soon found herself being under the guidance of the famed glass designer, Harold Bergen. When the time came to choose which medium she will pursue experience in, Anna Therese Johanne Höch decided to go with the glass design and graphic arts[3], avoiding the direction of fine arts. However, the young artist's development was suddenly put on hold as the World War I broke out and her country placed itself in the main role of what will prove to be the biggest human conflict to that point. Höch went back to her hometown in 1914 and worked for the Red Cross for some time. A year later, she returned to school, entering the graphics class of Emil Orlik at the National Institute of the Museum of Arts and Crafts. There, Anna Therese met Raoul Hausmann, a respected member of the Berlin Dada movement. This will eventually prove to be the key friendship of Höch's career.

Hannah Höch and the Berlin Dada

Since 1917, Höch was a vital and regular part of the Berlin Dadaist circle. Initially, she worked in the handicrafts department of the Ullstein Verlag's company called The Ullstein Press - here, she was in charge of designing dresses and embroidery patterns for a varied clientele. As a matter of fact, the influence of this early job and training can be easily seen in Höch's later work that was regularly referencing dress patterns and textiles throughout its appearance[4]. However, Hannah, as she chose to call herself by that point, had a hard time with finding a significant place within the early avant-garde art in the German capital. Although many artists such as Georg Schrimpf, Franz Jung and Johannes Baader believed women should have equal creative rights as male practitioners (at least as far as talking about it goes), many authors were reluctant to accept Höch within their ranks simply because of her gender[5]. For example, Hans Richter went as far as describing all of Höch's contributions to the Dada movement as the sandwiches, beer and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money. Of all the Dada artists in Berlin, Hoch was the only one that was pressured by her colleagues to find a real job. Höch was the lone woman among the Berlin Dada group, stranded within what everyone wanted to describe as a male creative world[6].

Among other things she did for the German Dada, Höch expanded the commonly accepted notion of what may and what may not be incorporated into a valid artwork

Hannah Hoch's Relationships

During all the years spent within the ranks of the Berlin Dada, Höch maintained a heavily strained love affair with the aforementioned Raoul Hausmann. Their relationship was quite turbulent because both of them had a bad temper, which was not helped at all by the fact Hausmann was already married and did not want to leave his wife despite Hannah constantly asking him to do so. According to the art historian Maria Makela, some altercations between the two even ended in violent episodes. Furthermore, these lovers had many conceptual fights about art and the role of women within this world. These stresses and fights culminated in the form of Höch's The Painter, an essay written during the year of 1920 that tackled the subject of an artist who is thrown into an intense spiritual crisis when his wife asks him to do the dishes. Hannah finally left Raoul Hausmann in the year of 1922, ending the seven-year long bond that definitely had its ups and downs[7]. If nothing else, Höch and Hausmann were one of the first pioneers of the art form that would come to be known as photomontage in years to come. In 1926, she began a relationship with the Dutch writer and linguist Mathilda ('Til') Brugman. The two lived and worked in the Netherlands where Höch met Kurt Schwitters and Piet Mondrian, among many others. It should be noted that Hannah and Mathilda never publčicly declared their involvement as being lesbian, instead opting to define it as a private love relationship.

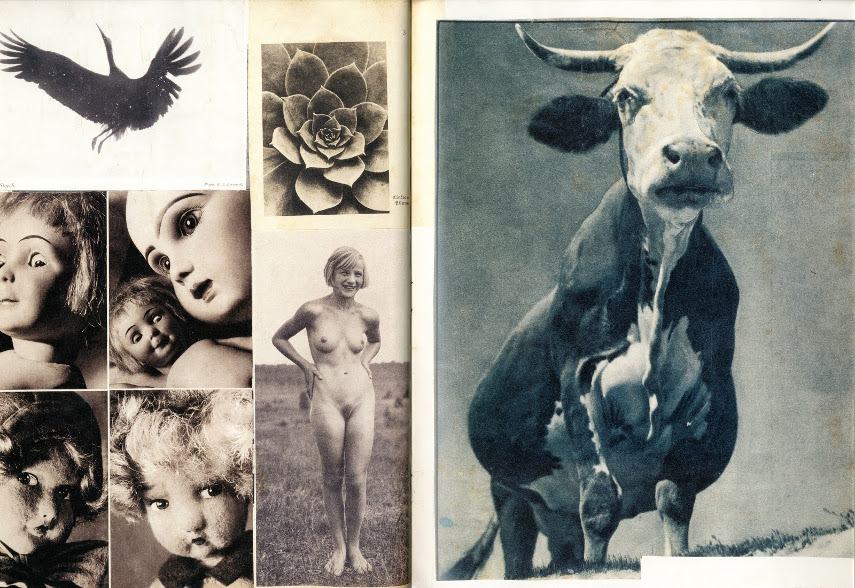

Hannah Höch was one of the key figures responsible for authoring the practice of collaging assorted photographic elements gathered from different sources to make a piece of art

World War II and Hannah's Later Years

During the year of 1935, Höch began a relationship with a businessman Kurt Matthies whom she later married. When the WWII started to set the flames of death all across the Old Continent, Hannah stayed in Berlin but kept an extremely low profile. She lived (if that can be called living) in Berlin-Heiligensee, a remote area located on the outskirts of the German capital, hiding in a small garden house. By that point, she was a notorious avant-garde artist, a feminist, an anti-government author and a publicly known lesbian - all the characteristics one would not want to have whilst living in the Third Reich. The Nazi's censorship of art had a massive influence on Höch and her art which was deemed as being degenerate and harmful to the German society. Since then, Hoch decided to take a step back, probably because she was finally too broken from all the obstacles that were placed in front of her for the majority of her life. And even though her work was not as acclaimed after the Second World War as the case was before the rise of the Third Reich, Höch continued to produce her photomontages[8] and collages[9] and exhibit them on the international stage until the time of her death in 1978 when she took her last breath in Berlin, the city she loved the most in this world.

Besides contributing heavily to the Dadaism and, indirectly, to all the following modern movements, Höch can also be described as a key feministic figure of the previous century

So Vital, yet Often Overlooked

Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for the name of Höch to be overshadowed[10] by some of the bigger artists that emerged from the early avant-garde art as this was a time when male-made artworks were much more recognized and by far outnumbered their female colleagues. However, despite this obviously stagnating her creativity by a fair amount, this occurrence only makes the work of Hannah even greater. Höch is not only responsible for pioneering some of the most important Dada and avant-garde art but is also the destination to which most feministic roads of the 20th century lead to. Her artistic criticism was a feministic milestone, a factor that weighed heavily on many aspects of gender issues. Furthermore, Hannas also provided us with interesting and evocative reflections on the industrial development and the very concepts of beauty. Ultimately, Höch was one of the most important female artists of the 20th century - if not of all art history.

References:

- Kamenish, P. K., Mamas of Dada: Women of the European Avant-Garde, University of South Carolina Press, 2015

- Höch, H., Orgel-Köhne, Kittner, A. E., Hannah Höch: Life Portrait: A Collaged Autobiography, The Green Box, 2016

- Höch, H., Luyken, G., Currid, B., Hannah Höch: Picture Book, The Green Box; First Edition, 2010

- Boswell, P., Makela, M., Lanchner, C., Höch, H., The Photomontages of Höch, Walker Art Center, Inc, 1996

- Hille, K., Hannah Höch, Independent Publication, 2016

- Anonymous, Hannah Höch, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2007

- Ades, D., Herrmann, D. F., Hannah Hoch, Prestel; First Edition, 2014

- Höch, H., Lavin, M., Cut With the Kitchen Knife: The Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Hoch, Yale University Press; First Edition, 1993

- Höch, H., Höch, G. A., Hoch Collages 1889 - 1978, Stuttgart: Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations, 1985

- Hudson, M., Hannah Hoch: The woman that art history forgot, The Telegraph, 14 Jan 2014

Featured image: Hannah Hoch - Ing on cardboard, 1958, Ing on cardboard signed and dated, 18 4/5 × 26 3/5 in, 47.7 × 67.5 cm, HUNDERTMARKartFAIR, San Augustin

All images used for illustrative purposes only.

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.