Over the weekend, the people who manage the SETI@home distributed-computing project announced it would be going on hiatus at the end of March. The project was one of the first efforts that successfully convinced home users to donate some of their free computing time to help with research, and its success spawned a large number of related projects.

While it's on hiatus, users with a fondness for distributed computing might take a look at Folding@home, which is trying to figure out the structures of proteins on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.

SETI sunset

The SETI@home's project page describes the reason for the shutdown simply. Over the years, home users have done so much processing that the team now has a large backlog of processed data to analyze. So, the researchers are de-prioritizing the management of the data distribution and focusing instead on looking at what has already been done in the hope of getting their analysis published in an academic journal. As a result, no more work units will be distributed after the end of March.

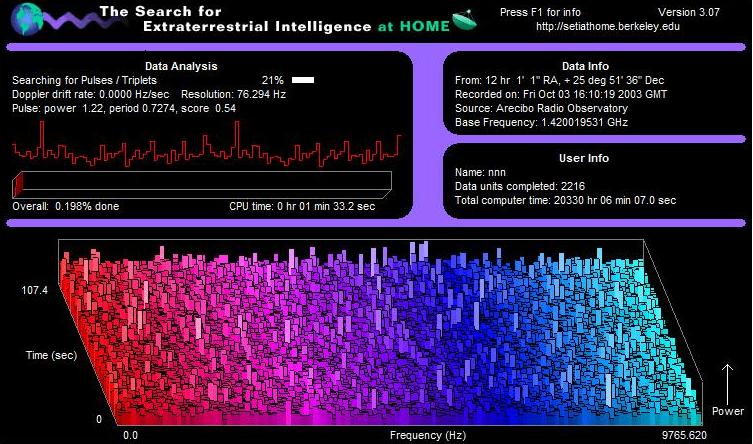

SETI@home was an extremely popular project in its heyday and helped define the parameters for successful distributed computing. It had an obvious public interest hook—find the first signs of little green men!—and packaged it in a screensaver that (although difficult for a non-expert to interpret) was visually appealing and gave its users the sense that work was getting done. I will readily admit that I installed it on the computers of a couple of labs I worked in.

Its success launched a variety of other distributed computing projects focused on things ranging from cracking encryption keys to tracing neurons. Additional projects have since gotten people to analyze data by eye, ranging from images of galaxies to old weather reports.

On the computing side, Ars readers were major contributors for a number of years, as distributed computing became gamified and hosted public leaderboards. For a while, we ran regular updates on our readership's progress (you can find some of them near the bottom of this page), and Ars still hosts a distributed-computing forum.

There was so much interest that researchers at Berkeley developed a distributed infrastructure and API that other projects could plug into. The Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing now hosts a large number of projects that run on multiple OSes and architectures, all generally focused on academic research in the sciences and math. SETI@home has just been another plugin for the BOINC architecture for a while; users who are still interested in distributed computing can simply choose another project.

The SETI@home project managers suggest that they're looking for other astronomers who might want to take advantage of the processing power that had been going toward the search for extraterrestrials. It's not clear whether that would be done through the existing SETI@home client or by redirecting people to a different BOINC plugin.

Elsewhere @home

If you are looking for an alternative distributed-computing project, Folding@home is looking for help with tackling an issue of major public importance at the moment: the structure of key proteins on the surface of SARS-CoV-2. The coronavirus uses these proteins to latch on to proteins on the surface of human cells, a key step in its ability to infect them.

Understanding the structure of this protein is a key to understanding the virus' vulnerabilities. While it won't help in the production of a general vaccine, it can be extremely useful in developing therapies. Once we know where this protein interacts with its receptor on human cells, we can start searching for small molecules that could bind in this same location, potentially blocking this interaction. Alternatively, we can potentially generate antibodies that bind to this site on the virus' protein. Either of these options can help people who are already infected, as they can limit the virus' ability to spread to new cells.

Fortunately, research on SARS-CoV-2 is moving incredibly quickly, and biologists have been keeping pace with the computers here. Structural details of the key protein on the surface of the virus have already been published, allowing researchers the chance to start considering ways of interfering with its infection.

That doesn't mean any results from Folding@home are now useless, though. The existing structure provides a valuable check on the results derived from computation, and it's much easier to try alternative configurations—complexed with proteins on the cell's surface, and even complexed with potential drugs, to give two examples—using computers than it is to confirm the results via biochemistry.

reader comments

102