Astonishing story of Australian camels. Why thousands of them are shot dead routinely

Australia has the world's largest herd of wild camels and lakhs of them roam in the wild. The govt is fed up with these camels, who aren't native to Australia, and has declared them to be a pest. But how did they reach the continent? And for what?

The year was 1606. Europe by now had established itself as the leader in the 'age of discovery'. Undertaking long overseas expeditions to 'discover' unvisited distant lands had gained currency by then. India was already 'discovered' via sea route, so were Africa, North and South Americas. It was in this backdrop that Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon made landfall in Australia on February 26, 1606 and became the first European to reach the continent.

In his first visit, Janszoon barely stayed in Australia, which back then was sparsely inhabited by the Aboriginals. Had he stayed put and ventured into the vast arid outback Australia, his experience of seeing the terrain may not have been very different from a similar venture today, albeit a major exception--Camels.

Four-hundred-and-forty-four years ago when Janszoon landed in Australia, the humped mammals were nowhere to be seen on the continent. Not a single one of them existed back then.

Cut to 2020, Australia has the world's largest herd of wild camels and their population is estimated to be about 3,00,000, spread across 37 per cent of the Australian mainland. Fed up with its camels, Australia has declared them to be a "pest" and treats them as an alien invasive species that must be urgently stopped from spreading.

The most widely used method to check their population is aerial culling in which thousands of wild camels are shot down by snipers using helicopters.

Around 2012, Australia was gunning down about 75,000 camels every year.

On Wednesday (January 8), Australian authorities started a five-day operation with a target to shoot down thousands of wild camels using snipers mounted on helicopters. The exact figure is unclear but media reports suggest it can result in anything between 5,000 and 10,000 dead camels.

The operation has drawn widespread condemnation world over, with many terming it to be inhumane.

But how did these camels reach Australia? And how does one explain their massive population explosion over the years?

TRACING THE AUSTRALIAN CAMELS

For close to 230 years after Janszoon landed in Australia, the continent didn't see any camel sauntering across its vast arid regions. The reason: camels aren't native to Australia. They reached the continent to fulfill a colonial necessity.

In the early half of the 19th century, the British wanted to explore the vast continent's hinterlands. In this, their horses proved to be unproductive owing to the terrain and dry weather conditions.

In 1836, the colonial government in New South Wales explored the possibility of importing camels from India. But it was only in October 1840 that a camel first walked on Australian soil, but it wasn't from India.

It was a one-humped dromedary (Camelus dromedarius). Four-six of them were to be imported from Canary Islands, however only one, named Harry, survived the long sea journey.

Harry too met an unfortunate end. He was shot after he accidently killed his own master during an expedition. One account of the incident goes that Harry's master, JA Horrocks, was riding the animal and simultaneously preparing to shoot a beautiful bird which he wanted to add to his collection. Harry, who was kneeling and aloof to this, moved his body causing an accidental fire that fatally injured Horrocks.

In a letter Horrocks reportedly writes, "(The bullet) took off the middle finger of my right hand and entered my left cheek, knocking out a row of teeth."

Twenty-three days later, Horrocks died due to infection, but not before ordering the so-called "ill tempered" Harry to be killed.

Harry's fate aside, import of camels continued and in December 1840, a male and a female camel were brought to Australia. What happened to them is not documented. Two more camels were brought the next year, and many more later on.

The bullet took off the middle finger of my right hand and entered my left cheek, knocking out a row of teeth.

Unlike horses, camels were well-suited to survive in dry regions of outback Australia. They were in demand as they could be used for travel and transportation during long journeys into the continent's interiors. Besides, their ability to carry on without drinking water for weeks was an added advantage for travels in dry regions.

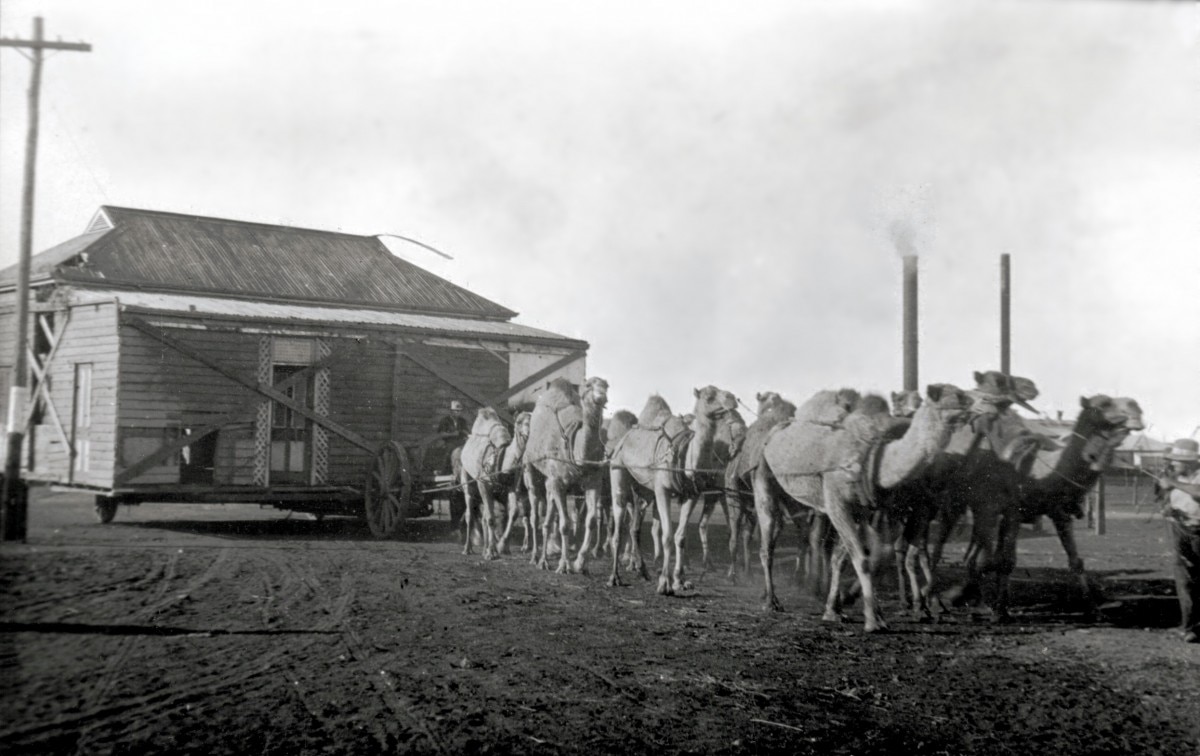

Thus, for decades, camels remained valuable assets in the everyday life of colonial rulers in Australia. Their dependence was such that by 1907, the British had imported nearly 20,000 camels into Australia, largely from India, Afghanistan and the Arab world.

With camels also came their riders, who were mostly Muslims. Over the decades, they played an important role in the development of Australia and also started integrating with the Aboriginal communities by initiating trade by bringing in goods like tea and tobacco.

THE EXPLOSION

Meanwhile, as these camels found a new home in a far-away land, the world of innovation moved on. By the dawn of the 20th century, use of motorised vehicles became popular and Australia wasn't untouched.

From 1920s, the population of domestic camels in Australia began declining as people started using vehicles and abandoned camels. Over the next decade, Australia saw a "wholesale abandonment" of domestic camels.

Once released in the open, these camels became feral and started multiplying rapidly.

In 1969, population of such feral camels roaming in outback Australia was estimated to be between 15,000 and 20,000. In the next 20 years, their population more than doubled. It was estimated that 43,000 feral camels inhabited Australia in 1988.

Between 2001 and 2008, the number of feral camels in Australia was pegged at 10,00,000 (1 million). These figures were later revised to 6,00,000 -- still a high number. Wildlife experts warned Australian authorities that if this population growth went unchecked, their number would double in 8-10 years.

Soon, the Australian government adopted the National Feral Camel Action Plan and began massive culling operations. By 2013, the camel count was brought down to about 3,00,000.

Today, feral camels are found across Western Australia, South Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory, covering nearly an area of 3.3 million sq km.

Thus, in the 180 years between their introduction in 1840 to the present times, camels in Australia have a come a long way: from being a valuable asset to a wild "pest".

ARE THEY A PROBLEM?

Nearly a century after their ancestors were 'freed' from human bondage, these feral camels today eat, sleep and roam around across the vast stretches of outback Australia.

But this is too simplistic a description.

The Aboriginals living in these areas complain that feral camels are cause for their misery as they aggressively compete with them and their cattle over the region's limited water resources.

The area inhabited by feral camels is also one of Australia's driest parts. Year 2019 was particularly harsh for the region as temperatures soared and rain betrayed it. As such, water, which anyways is scarce here, became scarcer.

WATCH | The problem of feral camels

The Aboriginals have been complaining that feral camels often guzzle up and pollute their water resources, leaving little or nothing for them and their cattle, besides routinely damaging fences and grazing lands.

Their other problems with camels include:

- Damage to culturally significant sites including religious sites, burial sites, ceremonial grounds, places (including trees) where spirits of dead people are said to dwell.

- Damage to vegetation and increased risks to biodiversity by competing with native animals.

- They disturb game species or get in the way of hunters.

- They cause yearly damage worth $10 million.

Thus, the Aboriginals and feral camels today find themselves positioned in a struggle for survival in a region with scarce resources.

THE ORDER TO SHOOT THEM DOWN

On January 8, 2020, culling operation began in South Australia's remote areas and by the end nearly 10,000 camels may be shot down. The order was passed by the local government, Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands.

In a statement APY said, "The feral camel groups are putting pressure in the remote Aboriginal communities in the APY Lands and pastoral operations as the camels search for water."

It said the camel groups "pose threats" to communities, scarce water resources and are destroying and eating up food supplies, necessitating "immediate camel control".

Justifying the culling in another statement on January 7, APY said it is an "urgent response" to threats posed to the local communities by an increase in the number of feral camels due to drought and extreme heat.

"There is an extreme pressure on remote Aboriginal communities in the APY Lands and their pastoral operations as the camels search for water," Richard King, APY's general manager, said.

Meanwhile, APY Executive Board's member Marita Baker has said her community has been "inundated by feral camels" that are "roaming the streets looking for water".

"We are worried about the safety of the young children. They think it is fun to chase camels, but it is of course very dangerous," she said.

"We have been stuck in stinking hot and uncomfortable conditions, feeling unwell, because the camels are coming in and knocking down fences, getting in around the houses and trying to get to water through air conditioners," Baker said.

Culling of feral camels in Australia using helicopters has become a routine practice and is one of the three measures used to check their population (the other two are culling from ground and exclusion fencing).

There is an extreme pressure on remote Aboriginal communities in the APY Lands and their pastoral operations as the camels search for water.

As on 2012, an average of 75,000 feral camels were being reportedly culled every year in Australia.

In 2013, Lyndee Severin, whose team used to shoot down camels from helicopters and leave them to rot, told BBC, "It's not something that we enjoy doing, but it's something that we have to do."

DOESN'T NATURE CHECK THEIR POPULATION?

Camels in Australia are blessed by nature. They have the stamina and endurance to survive in harsh conditions, and the very sparsely populated outback means they haven't faced much competition from other species.

Commenting upon their survival instinct, the National Feral Camel Action Plan states that these camels are hardly affected by any diseases or parasites.

"Diseases and parasites don't have a major impact on feral camels in Australia. Diseases that can affect camels such as Brucellosis and Tuberculosis, camel pox or camel Trypanosomiasis are not present in Australian camel populations. Similarly, parasitic impacts on Australian feral camels appear to be minimal," the plan stated.

The other factor that works strongly in their favour is that the Australian landscape hardly hosts any predator for camels. The dingo is believed to be the only potential predator, but it too attacks only the newborns and calves.

Thus, besides humans, who occasionally hunt them for meat, camels in Australia hardly have enemies--a win-win situation. No wonder their population has not just ballooned but exploded. Literally.

Other facts:

- Average lifespan: 25-40 years

- Mortality rate: 6-9 per cent/ year

- Reproduction: Cows reach sexual maturity at 3-4 years of age

- Gestation: 336-405 days

- Reproductive lifespan: Around 25 years

- Calving interval: Around 2 years

OTHER OPTIONS STRUGGLE ALONG

In recent years Australia has also explored other ways of controlling camel population, like setting up infrastructure to facilitate export of camel meat and rearing them in farms.

The fact that Australian camels enjoy a near disease-free status greatly enhances their suitability for commercial use in the meat industry and even for live export.

Government estimates suggest around 5,000 camels are slaughtered for human consumption every year in Australia.

Other interventions include domestication and making use of products like camel milk, hair etc or setting up themed parks offering camel rides to tourists.

But presently these measures are uneconomical and have failed to pick pace. The National Feral Camel Action Plan had found that though there is potential in these industries, their size is so small that they aren't geared to handle the large camel population.

As for Australia, it says killing thousands of camels from helicopters is practically the best and most "humane" way to check their numbers to protect interests of Aboriginal communities and native species.

- Read more from Mukesh Rawat's archive, follow him on Twitter or subscribe to his updates on Facebook.

ALSO READ | Drought-stricken Australia to cull 10,000 camels for drinking too much water. Twitter is angry

ALSO WATCH | Details of Australia's feral camel management programe