From its earliest beginnings, punk as a youth cult was viewed as a social nuisance in cities – irritating but tolerated. But the battle lines were truly drawn in what became a focal point for the nascent hardcore scene: early 1980s Los Angeles.

“LA was a sketchy place then,” recalled Dave Markey, whose 1982 documentary The Slog Movie captured the LA punk scene in all its raw, ragged glory. Speaking in a 2011 interview, Markey, who was a teenager at the time, added: “You wouldn’t walk down certain streets. But it was also like a playground for us.”

A mass cleanup was also under way in preparation for the 1984 Olympics, and the burgeoning, unsightly punk subculture was seen as a civic issue. “We’re trying to sanitise the area,” a police captain from the LAPD’s Olympic planning committee told the Los Angeles Times in the runup to the Games. At first, the police were focused on transients and other street-dwellers, whom they wanted to remove from the public eye. But the city’s punks quickly landed on their radar.

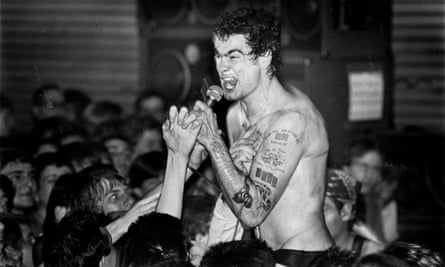

Concerts – legitimate and informal – were closed down with impunity. The emboldened LAPD rarely showed restraint, despite the young age of those they were battling. In fact, according to Henry Rollins, singer of LA punk flag-bearers Black Flag, it was the youthfulness and striking appearances of the punks that made them such a target. “I think this was one of the things that made the LAPD hate punks and assault them with regularity,” he would write nearly 30 years later. The song Police Story told its own tale: “This fucking city / Is run by pigs / They take the rights / Away from all the kids”, while Circle Jerk’s class-based disgust directed at the denizens of Beverly Hills (“All the people look the same / Don’t they know they’re so damn lame?”) doubled down on the rejection and isolation of those who felt they were being sidelined in Reagan’s America.

As a host of cultural historians will attest, punk never died, it just went underground. Mutating into hardcore, it retreated to the basements, the garages and the backstreet dives – but like a weed pushing through the cracks, it has fought to find its place in the hostile environment of the modern city. Punk’s hardcore iteration in the 1980s, unlike the attention-grabbing extroverts of the 1970s, was utilitarian, self-sufficient (or “DIY”, to use the movement’s lingua franca), and very much a product of its environment. Hardcore punks were a Suburban Disease, the Urban Waste, the Subterranean Kids. They spoke of Social Unrest, a Mad Society and URBN DK.

But while they wore those municipal scars as a badge of honour, they refused to be bound by them. First came the job of recasting their own environment. Then – as their confidence grew and the desire for social justice became more than just a slogan on a jacket – the cities themselves would need to change. For the politically minded and socially motivated punk, the collectivist principles of Crass, rather than the nihilism of the Sex Pistols, would reflect their actions.

The battles would be waged across the US – and the rest of the world, to a greater or lesser degree. Punks in Colombia and Indonesia, where run-ins with military death squads or sharia police were a daily occurrence for those sporting pink mohawks, could quite rightly scoff at Black Flag’s police issues. But in the west, while the stakes were rarely life and death, the struggles over who owned the city were just as fiery.

Of course, then as now, the fulcrum of punk and hardcore rested on the music. For the scene to survive, hardcore bands needed places to play – and in venues free from intervention by authority figures or age restrictions (in the US, the drinking age of 21 would exclude a good 80% of the audience).

This meant a cat-and-mouse game of searching out friendly or unsuspecting venues – school gymnasiums, social centres, youth clubs and even war veterans’ meeting halls – and playing the hell out of them until their welcome wore out. Given the unfettered, rowdy nature of the performances and audiences, it often wore out midway through the show: the authorities were often called, and Black Flag’s Police Story would be played out in microcosm.

Something more concrete was needed. In the late 80s and early 90s, the scene’s dogged footsoldiers founded a series of autonomous spaces that have become global beacons of punk’s countercultural ethos: the 1 in 12 Club in Bradford; Berkeley’s 924 Gilman Street; New York’s ABC No Rio. Although primarily known for its function as a music venue, the 1 in 12 began life as a social club promoting anarchist values. Its four stories host a recording studio, bar, cafe and extensive library of anarchist texts. ABC No Rio offered a dark room, silk-screening facilities and a public computer lab in addition to hosting concerts, exhibitions and film screenings.

It’s somewhat surprising, then, that London has taken so long to establish its own autonomous space – and it was only due to the efforts of a small group that, in 2015, DIY Space for London was established.

“It was always about bringing the threads of music and activism back together in one space and seeing what could happen as a result,” says DIY Space co-founder Bryony Beynon of the culmination of a three-year fundraising campaign born of the eternal quest for a place to play music without interference.

Tucked away in an unfashionable corner of south London, DIY Space for London seems safe for now – “The project is seriously enormous,” says Beynon, noting that they now have 6,000 members who run the venue collectively – but cities change.

When 924 Gilman Street was established in the dusty backstreets of Berkeley in the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid-80s, it was hard to imagine that gentrification would ever become an issue. But as the tech industry boomed, those ugly warehouse districts suddenly became eminently desirable. Gilman Street found itself nestling alongside craft breweries, barbecue joints and – that vanguard of gentrification – a branch of Whole Foods. The venue’s future has only been secured by countless depositions to the local council, numerous benefit gigs and even the intervention of punk-rock millionaires Green Day.

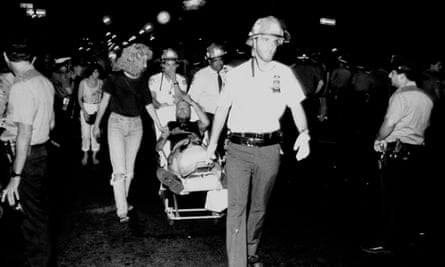

Punk’s war against gentrification may be long lost in Manhattan’s East Village but one of its most notorious flashpoints is still celebrated. In 1988, Tompkins Square Park, home to a de facto homeless shelter, was the site of a protest – with punk bands performing – against the city’s plans to sanitise the streets, as LA had done a decade earlier. Responding to noise complaints, the police moved in. All hell broke loose.

Over two days, punks, protesters and bystanders battled with NYPD officers whose brutality was so well-documented – not least by poet Allen Ginsburg – that it led to condemnation by the New York Times and mayor Ed Koch. Sixteen years later, in 2004, a Tompkins Square anniversary concert – featuring the punk band Leftover Crack – was somewhat more in keeping with the newly rarified surroundings of the East Village: there was only one attempted arrest, for an open-container violation, and a minor scuffle between punks and cops. “It was a confrontation,” said a NYPD spokesperson when asked about it. “I don’t know if ‘riot’ is the right word.”

Modern-day Washington DC, too, has found itself reliving one of the more infamous chapters of its rich punk history. Activist Robin Bell projected the phrase “Experts agree: Trump Is a Pig” on to the side of the Trump International hotel – a nod to the notorious 1987 poster campaign of Jeff Nelson, drummer of Minor Threat (the band that gave the world “straight edge”, the drug and alcohol-eschewing sub-group of hardcore punk).

Nelson and his cohorts, outraged by the conservative endeavours of Reagan wingman Edwin Meese, covered the city with posters declaring: “Experts agree: Meese Is a Pig”, prompting bemused conversations in many a Beltway office. Then 6,000 T-shirts were printed and sold, one of which became the subject of an ACLU legal threat when a bike messenger wearing it was denied entry into the Justice Department.

Nelson’s slogan was knitted into DC’s collective consciousness. Looking back now, he says: “Everyone was convinced we had engineered the whole thing, but we had nothing to do with it. The whole thing had a life of its own.” It sums up the essence of punk activism in cities – a rock thrown into a still pond to see how far the ripples carry. At its most potent, those ripples become waves.

One of those rocks has been Beynon’s work creating Good Night Out, a campaign that encourages bars and venues to tackle and prevent harassment. It’s an idea that has spread from south London to North America. “Watching the campaign grow from a few conversations has been amazing,” she says. “When you’re indoctrinated as a teenager to [punk’s] idea that you can do anything and get away with it, it’s hard not to have this leak into other areas of your life.”

Similarly, Zoe Dodd, a harm reduction worker and veteran of Toronto’s punk scene, made headlines last year when – shocked by a 327% increase in overdose deaths since 2008 – she set up a drug harm reduction workshop in Faith/Void, the city’s autonomous punk space. It was a triumph of DIY ethics and has already been emulated in Montreal and Vancouver.

In Indonesia, the folk-punk collective Marjinal have taken this philosophy to the streets of Jakarta: they turned their suburban rented house into an art collective, creating works on their front lawn to reassure neighbours that the urges of these tattooed punks with the strange haircuts were creative rather than destructive. They hand out musical instruments to street kids, hoping to instil in them a sense of purpose and prevent them from being drawn into the cycles of drugs and prostitution.

All this is done despite persecution from authorities who, in some of the more conservative areas of the country, have no problem rounding up punks, shaving their heads and sending them off to sharia boot camps. When I met Marjinal during a tour of Japan, they were raising money to establish – what else? – a music venue. The locations and languages may change, but the struggles are universal.

And they continue. At the turn of the year, activists working for Food Not Bombs – an organisation with close ties to the punk scene through benefit gigs and record sales – were arrested for helping to feed the homeless in Florida. The story spread like wildfire across social media, and the resulting outcry resulted in Tampa authorities vowing to change bylaws concerning community outreach programmes. In the 21st century, street-level punk activism finds traction in the realm of social media just as much as it does on the streets proper.

It has also made inroads into establishment politics. Jello Biafra, former frontman of the Dead Kennedys, started the trend in 1979 when he ran for mayor of San Francisco. Part prank, part publicity stunt, Biafra’s campaign saw him gain more column inches than votes, but the die was cast.

Bob Barley, owner of punk and noise record label Vinyl Communications, ran for mayor in his home town of Chula Vista, campaigning on an anti-big business, pro-local business platform. “To me, running for mayor was the equivalent of putting out an LP. That was the punkest thing I could do,” he said. “I came fifth out of 11 candidates … ahead of a pro-life guy who was endorsed by the Republican party.”

But the real punk-politics success story belongs to Doc Dart, singer of the Crucifucks (not something widely publicised during his campaign), who ran for mayor in Lansing, Michigan in 1989. The distant third in a 50-50 race between two establishment candidates, he realised that he held the balance of power with the thousand or so votes he’d drummed up – so he traded his endorsement for the promise of a rape crisis centre being created in the city, the issue he originally ran on.

“[The mayor-elect] put me on a committee, we plotted the thing along, and [the rape crisis centre is] in a hospital here in town,” he told the punk magazine Dear Jesus in 1991. “It worked out better than being elected, actually … So very much can get done if you just put some work in on something, even if it’s just to take a can of corn down to the food bank.”

More than a quarter of a century later, that sentiment still rings true with Beynon, no stranger to London’s establishment figures during her time as an anti-harassment campaigner. “If I have to don a bit of a disguise to get a seat at a table, then I’m going to do it,” she says. “I would rather hold my nose and engage with a system that stinks than turn away completely.”

She argues that it can be radical to try to change cities by tiny degrees every day. “Eventually the whole picture will have changed right under their noses.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion